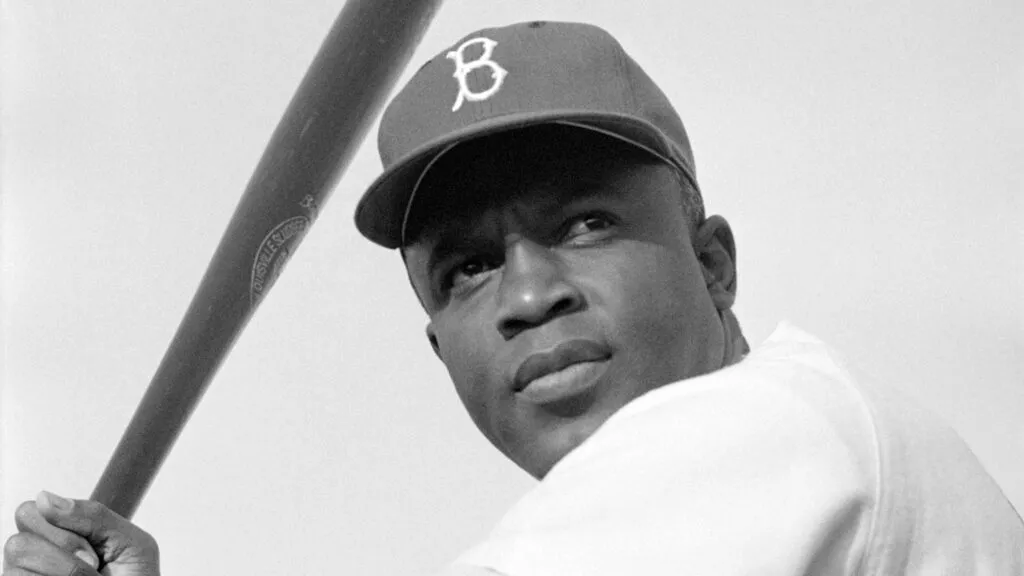

This is going to be a big year for me. After more than six years of shooting for a chance to manage a major-league baseball club, I’ve finally got one and I’m very happy about it. I’m grateful that the Cleveland Indian organization has enough confidence in me to let me lead its team on the field this year. Now it’s up to me to do the job.

That job, successful managing, is to me mostly a matter of caring about people and helping them to make the most of their own abilities. In that way, I suppose, managing baseball is not much different from any other job—or any other part of life actually—where working and living with other people is involved.

To me, no man did the job any better than Birdie Tebbetts, who was managing Cincinnati when I broke into the majors in 1956. Birdie is the best example I know of a man who cared deeply about the members of his team and wanted the best for them. And how he was loved by his players! The Bible says that love is kind and patient, full of hope and trust; if you believe that, then Birdie was a guy who really loved his players, too.

I remember my rookie year; I was 20 and scared stiff, though I tried not to show it. Birdie put me in left field for the opening game of the 1956 season against the Cardinals, and I got two hits in three at-bats. Though we lost, 4-2, on Stan Musial’s two-run homer, I came away from the game feeling good. Then I went into a tail spin, getting only two hits during my next 23 at-bats. I was really confused and beginning to doubt I was ready for the big leagues.

Before a Tuesday night game at old Crosley Field in Cincinnati, Birdie put his arm around me and said, “Frank, this guy they’re pitching tonight is one of the best, and he fools some of the veterans. I’m taking you out of the line-up tonight so you can watch him. You’ll be able to do the job against this pitcher eventually, but I don’t want you to get discouraged. I don’t want you to lose faith in yourself. You’re going to be a great player, but it takes time. I’ve seen too many players ruined by rookie slumps; I don’t want that to happen to you.”

And so I watched from the bench that night, secure in the knowledge that my manager was doing something for my own good, that he really cared about me. A few games later, Birdie put me back in the line-up, and I got a couple of hits. From then on, I started to play well. I hit .290 for the season and finished second in home runs in the National League, hitting 38. Birdie’s sensitive handling of me at a crucial time, I’m convinced, was the key. If he hadn’t really cared, and shown it, he would have let me play my way right back to the minors.

I want my players to know I care about them as people. And people who care about one another support one another; they work, hope and dream together.

Another thing about Birdie was his readiness to share his experience with the players. Always surrounded by rookies on the bench during a game, Birdie was constantly teaching.

“Now watch the runner, boys. He just got the sign to steal.”

“Let’s move our third baseman and shortstop back. This guy couldn’t drag a bunt with a thirty-foot bat.”

“Watch the pitcher. He’s telegraphing his curve ball.”

Anyone who sat beside Birdie for a whole game couldn’t help but learn something new. And that’s the way he wanted it.

George Powles, the manager of the Oakland American Legion baseball team on which I played as a teen-ager, was another manager who knew how to share himself with others. I was the youngest of ten kids in my family and fatherless after the age of eight, so I was ripe to respond to a man like George, who saw some potential in me. On weekends we would begin playing ball at nine o’clock in the morning and continue until dark. After practice, as if we hadn’t had enough baseball, George would invite us over to his house for sandwiches and baseball talk. What a student of the game he was!

One of the most memorable, and practical, things George told me came one day when I struck out on a fast ball because I wasn’t ready for that pitch, and it was by me before I could get the bat around. Afterward, George took me aside and said, “Always anticipate the fast ball. That’s the one that arrives at the plate the quickest. If the pitch isn’t a fast ball, you can adjust.” It was several years later in the major leagues before I heard that simple bit of logic repeated.

Another thing I believe is important in dealing and working with people is good communication, keeping those lines open all the time. Misunderstanding can almost always be traced to a lack of openness, directness between people.

Fred Hutchinson was one of my managers at Cincinnati early in my career, and although he knew the game as well as anyone, he was a tight-lipped leader. More than once, that lack of communication created some problems.

Once I got hit on the arm with a fast ball, and my arm swelled to twice its normal size. I had trouble swinging a bat; my arm hurt whenever I tried. Finally Fred told me he was taking me out of the lineup; he wanted to give my arm some rest.

The trainer worked on it and I did rest for a couple of games. I was improved enough to play, but because Fred didn’t engage in conversation easily, his players, especially one as young as I was, kept their distance and were often reluctant to volunteer information.

We were playing Houston and had fallen behind by two runs. In the last of the ninth, when we loaded the bases with one out, Fred needed a right-handed pinch hitter, and I figured he would ask me. Instead, he motioned to another player. That player, not a particularly good hitter, grounded into a double play and we lost the game.

Afterward, a reporter wondered why I hadn’t pinch hit. “Does your arm hurt too much?” he asked me.

“No,” I told him. “I could have batted, but I wasn’t asked.”

He wrote that in his story, and the next day Fred called me to his hotel room to tell me, very forcefully, what a mistake I’d made. The whole affair taught each of us a lesson, I think, for we seemed to get along better after that, and I came to appreciate Fred’s other qualities that made him a good manager.

Since then I have made a vow to myself to stay in touch with my players. Hearing from them is as necessary as their hearing from me—just as keeping communication lines open between parent and child, worker and employer, neighbor and neighbor, is important.

As a matter of fact, it’s really remarkable how much managing a team of ballplayers is like managing one’s own life—caring, sharing and communicating with others. And I’m sure that it’s because getting along with other people is such an important part of both. That’s why I think everyone should know something about managing.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.