My journey into forgiveness began with a phone call, a breathtaking story and a question.

It was 2002. I’d spent the previous year in a whirlwind of promotion for my first book, Seabiscuit, and was taking some time off. One day, I found myself thinking about a man named Louie Zamperini.

Researching my book, I’d stumbled upon references to an odyssey that he’d survived in World War II. Though I’d only heard bits of his story, I was intrigued, and jotted his name in my notebook. When I finish this book, I thought, I’ll try to find him.

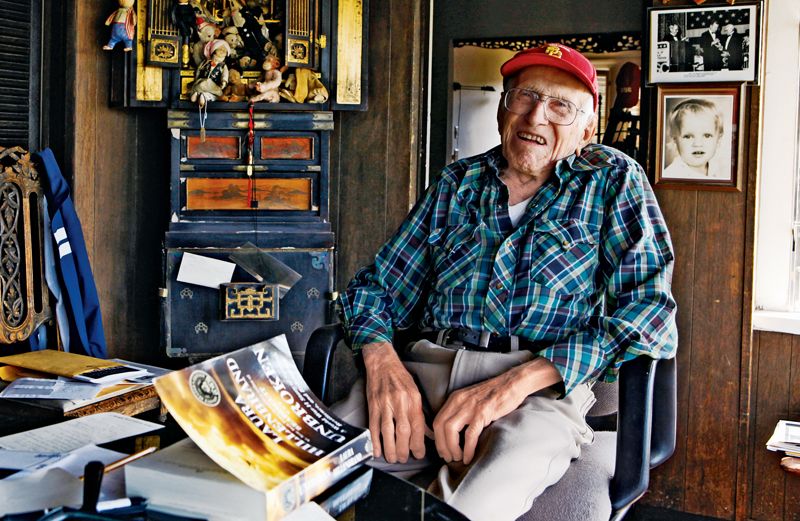

That day in 2002, I did a search online for Louie and discovered that he was alive, in his mid-eighties, living in California. I wrote him a letter. He sent a warm reply, so I called him.

Over the next hour, he told me the most amazing survival story I’d ever heard, a tale that included a plane crash, shark attacks, and capture and torture by the enemy. But what fascinated me even more than his story was the way Louie told it.

He was infectiously cheerful, speaking of his captors’ cruelty without a trace of bitterness. I asked how he could speak so easily of such vicious men. His answer was simple: “I’ve forgiven them.”

I was hooked. My mind began turning on a question: How does a man forgive what is seemingly unforgivable? In search of the answer, I began a seven-year journey through his life, a journey that culminated in my book Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption.

The more deeply I understood what Louie had endured, the more wondrous his forgiveness seemed.

As a boy in California in the 1920s and early 1930s, Louie was an incorrigible delinquent. Then he discovered that he had an extraordinary talent for running. He became a world-famous track phenomenon, competing in the 1936 Berlin Olympics when he was still a teenager.

World War II began, and Louie set aside athletics and joined the Army Air Corps. He was stationed in Hawaii as a bombardier, fighting harrowing air battles against the Japanese.

On May 27, 1943, Louie and his crew took off to search for a missing bomber. Far out over the Pacific, engine failure sent their plane plunging into the ocean. Trapped by wires in the wreckage, Louie passed out.

When he came to, the wires were gone. He swam to the surface and climbed onto a raft, joining two other survivors. They’d sent no distress call, and no one knew where they were.

For weeks the men floated, followed by sharks, surviving on rainwater and the few fish and birds they could catch. On the twenty-seventh day, a plane appeared. Louie fired flares, and the plane turned toward them.

But it turned out to be a Japanese bomber, and its crewmen fired machine guns at the castaways. Louie leaped overboard.

He had to kick and punch the circling sharks to keep them away until the firing stopped and he could climb back up onto the raft. Over and over the bomber returned to strafe the men, sending Louie back into the shark-infested water.

By the time the bomber flew off the raft was riddled with bullet holes and was starting to sink. Amazingly, none of the men had been hit, but the sharks tried to drag them away. Beating them off with oars, the men frantically patched the raft and pumped air into it. Finally the sharks left.

On they drifted, starving. One man died; Louie and the other crewman hung on. On the forty-sixth day, they saw a distant island. They rowed toward it. When they were only yards from shore, a Japanese boat intercepted them.

For the next two and a quarter years, Louie was a captive of the Japanese military. First he was held in a filthy cell, subjected to medical experiments, starved, beaten and interrogated.

Then he was shipped to prison camp in Japan, where he was forced to race against Japanese runners, winning even though he knew he’d be clubbed as punishment. He joined a daring POW underground, stealing food and circulating information to other captives.

It was in prison camp that Louie encountered a monstrous guard known as the Bird. Fixated on breaking the famous Olympian, the Bird beat Louie relentlessly and forced him to do slave labor.

Louie reached the end of his endurance. With his dignity destroyed and his will fading, he prayed for rescue.

When the atomic bombs ended the war, the Bird fled to escape war-crimes trials, and Louie was saved from almost certain death.

He went home a deeply haunted man. He had nightmares of being bludgeoned by the Bird. Trying to rebuild his life, he married a beautiful debutante named Cynthia, but even her love couldn’t blot the Bird from his mind.

He sought solace in running, but an ankle injury, incurred in POW camp and exacerbated by the Bird’s beatings, hampered him. Just as he was reaching Olympic form again, his ankle failed. His athletic career was finished.

Devastated, he started drinking. He had flashbacks: The raft or the prison camp would appear around him, and he’d relive terrifying memories. He simmered with rage, provoking fistfights with strangers and confrontations with Cynthia.

He couldn’t shake the sense of shame that had been beaten into him by the Bird.

Louie thought God was toying with him. When he heard preachers on the radio, he turned it off. He forbade Cynthia to go to church. He drank more and more heavily. In time, Louie’s rage hardened into a twisted ambition: He would return to Japan, hunt down the Bird and strangle him.

It was the only way he could restore his dignity. He became obsessed, trying to raise money for the trip, but his financial ventures kept failing.

One night in 1948, Louie dreamed he was locked in a death battle with the Bird. A scream startled him awake. He was straddling his pregnant wife, hands clenched around her neck. His daughter was born a few months later.

One day, Cynthia found him shaking the baby, trying to stop her from crying. She snatched the baby away, then packed her bags and walked out.

In the fall of 1949, Cynthia made a last effort to save her husband. She asked Louie to come to a tent meeting in Los Angeles, where a young minister named Billy Graham was preaching.

For two nights, Louie sat in that tent, feeling guilty and angry as Graham spoke of sin and its consequences, and God bringing miracles to the stricken.

On the second night, Graham asked people to step forward to declare their faith. Louie stood up and stormed toward the exit. But at the aisle, he stopped short.

Suddenly he was in a flashback, adrift on the raft. It hadn’t rained in days, and he was dying of thirst. In anguish, he whispered a prayer: If you will save me, I will serve you forever. Over the raft, rain began falling. Standing in Graham’s tent, lost in his flashback, Louie felt the rain on his face.

At that moment Louie began to see his whole ordeal differently. When he’d been trapped in the wreckage of his plane, somehow he’d been freed. When the Japanese bomber had shot the raft full of holes, somehow none of the men had been hit.

When the Bird had driven him to the breaking point, and he’d prayed for help, somehow he’d found the strength to keep breathing. And that day on the raft, he had prayed for rain, and rain had come.

Louie’s conviction that he was forsaken was gone, replaced by a belief that divine love had been all around him, even at his darkest moments. That night in Graham’s tent, the bitterness and pain that had haunted him vanished.

A year later, Louie went to Japan. He was a joyful man, his marriage restored, his nightmares and flashbacks gone, his alcoholism overcome. He went to a Tokyo prison where war criminals were serving their sentences.

He hoped to find the Bird, to know for sure if the peace he’d found was resilient. But the Bird wasn’t there. Louie was told that the guard had killed himself.

Louie was struck with emotion. He was surprised by what he felt. It was not hatred. Not relief. It was compassion. Louie had found forgiveness.

Louie Zamperini’s life is a journey of outrageous fortune, ferocious will and astonishing redemption. For me, what gives his story lasting resonance is the light it sheds on the cost of victimization and the mystery of forgiveness.

What the Bird took from Louie was his dignity; what he left behind was a pervasive sense of helplessness and worthlessness.

As I researched Louie’s life, interviewing his fellow POWs and studying their memoirs and diaries, I discovered that this loss of dignity was nearly ubiquitous, leaving the men feeling defenseless and frightened in a world that had become menacing.

The postwar nightmares, flashbacks, alcoholism and anxiety that were endemic among them spoke of souls in desperate fear.

Watching these men struggle to overcome their trauma, I came to believe that a loss of self-worth is central to the experience of being victimized, and may be what makes its pain particularly devastating.

Anger is a justifiable and understandable reaction to being wronged, and as the soul’s first effort to reassert its worth and power, it may initially be healing. But in time, anger becomes corrosive.

To live in bitterness is to be chained to the person who wounded you, your emotions and actions arising not independently, but in reaction to your abuser. Louie became so obsessed with vengeance that his life was consumed by the quest for it.

In bitterness, he was as much a captive as he’d been when barbed wire had surrounded him.

This is why forgiveness is so liberating. But how is it found? For Louie, it lay in resurrecting his dignity, seeing himself not as the wretched creature that the Bird had striven to make of him, but as the object of God’s infinite love.

His self-respect and sense of power reborn, he finally had the strength to let go of his hatred.

I talked to other former POWs who forgave their captors, and for each, forgiveness seemed to follow a return of dignity. Each man found it in his own way, guided by his history and his pain. Louie’s story doesn’t represent the only way out of bitterness. There is no one right path to peace.

Forgiveness is a complex, elusive mystery, and one man’s story can only begin to unravel its secrets. But I take from Louie’s life one beautiful, undeniable truth.

Even when a man suffers the most soul-shattering of abuses, even when he seems hopelessly bound by resentment, forgiveness can still find him and set him free.