To convert the last-place Pittsburgh team into a pennant winner, Branch Rickey faces his toughest job in 50 years of baseball. The Pirates executive who has built winning teams at St. Louis and Brooklyn admits he has never worked harder, doctor’s warnings notwithstanding.

To him the passage, “In the sweat of thy face shalt thou earn thy bread” (Genesis 3:19), is more of a benediction than a penalty.

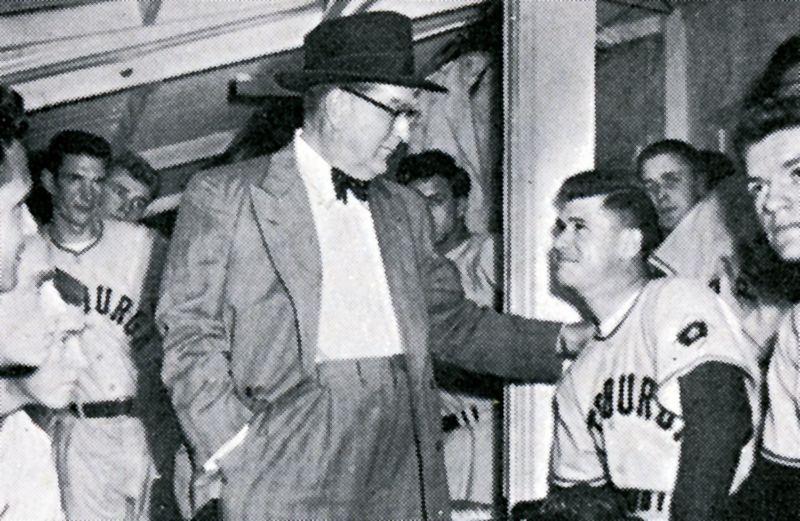

A working day for Rickey means endless personal consultations (press, players, friends) and long-distance calls. At the ball park he dictates comments on player performance to his personal assistant, Ken Blackburn.

A pitcher, warming up, can’t control his fast ball. Out comes the Rickey wallet. “This ten-spot is yours if you hit it with your fast ball,” Rickey tells him, placing the green bill on the ground in front of the catcher. The determined pitcher aims at the bill, throws above it by several feet.

“You see,” says Rickey, making his point, “to control your fast ball, you’ll have to aim it lower.”

A descendant of pioneers, Branch Wesley Rickey was born on a farm in Stockdale, Ohio. From his father, who had quite a reputation as a wrestler, Branch inherited his athletic ability.

“My father and mother never went to high school or college,” Rickey states. “What they had came out of a laboratory of testing Christ’s teachings.”

Rickey has never known anything but effort. He taught himself Latin and mathematics, worked at odd jobs to pay for his education at Ohio Wesleyan University. After graduation he played professional football, broke his leg, and then entered baseball as a catcher.

His big chance to play in the Major Leagues came with Cincinnati, but for reasons of personal conviction, he refused to play ball on Sunday. The baffled Cincinnati manager argued, finally released him. To this day, Rickey will not attend a baseball game on Sunday.

In Lucasville, Ohio, he met a girl named Jane Moulton, the daughter of a store proprietor; young Rickey proposed more than a hundred times before she accepted. The newlyweds scrimped through hard times, and Branch’s siege with tuberculosis, before he started his executive career in baseball with the St. Louis Browns.

Rickey has a deep respect, almost reverence, for women. When his peppery, 99 year-old mother-in-law, who loved to sing hymns, was on her deathbed, she and Mr. Rickey sang them together far into the night.

Much has been written about Branch Rickey, but only close associates and friends really know him. Bob Cobb, a close associate and President of the Hollywood Stars, tells of a camping trip in Colorado.

At night he, Branch and a few others were in sleeping bags “so close to the stars we could almost touch them,” Cobb said. “We talked about astronomy, then Branch started in on God and the universe. I’ll never forget it.”

At Amherst College last winter, during a discussion on ethics in sports, Rickey made this statement of belief:

“We’ve talked a lot about right and wrong. When you come down to it, though, what can we really believe? If I strip away all theories, philosophies and books on ethics, many of which are good, I always come to one basic belief … that Jesus was so perfect in His teaching and Life that I attribute to Him Divinity.”

Like any important figure who acts from convictions, Rickey is a target of critics, perhaps the more so because he does not lash back. He has to make decisions which are occasionally unpopular with fans and press. Yet he states:

“I would feel unworthy if adverse or unjustified criticism affected my decision or dulled the edge of my courage.”

The rich, booming Rickey personality can also explode unexpectedly. A political science teacher recently told him, “I want to be fair to other governments, so I expose the weaknesses of democracy and compare them to the strong points of Marxism and other political philosophies.”

Nonplused, Rickey asked him, “Can you quote the Preamble to the Constitution?”

The teacher said tie didn’t think all that was important.

For several moments the Pittsburgh General Manager eyed him with the famous Rickey scowl. Then in a rich voice, he began to repeat word for word, “We the people of the United States…”

Rickey hates disloyalty, deceit, hypocrisy, and demands honesty of his employees above all else. But he can be forgiving.

Last January he appeared as a witness in a Pittsburgh courtroom, where a man was facing jail for attempting to extort money from a Pittsburgh ball player. The prisoner was young, penitent, scared. Rickey eyed him intently, took the stand, and in a moving speech urged leniency. The young man was put on probation.

Rickey is most famous as a baseball pioneer. Seven years ago he paved the way for Jackie Robinson to become the first Negro to play in the Major Leagues. Many standard practices in baseball today (the farm system, sliding pits, etc.) are Rickey innovations.

During spring training last March at Fort Pierce, Florida, a reporter popped this question, “Mr. Rickey, you’ve been in baseball a long time. What has been your greatest thrill?”

Rickey was silent for a moment, looking at some 70 Pittsburgh players working out, many just kids, who with their great promise represented his hopes and dreams. The 72-year-old baseball executive, with his black hair and his bouncing energy, looked as young as any of them.

“My greatest thrill?” Rickey repeated. “It hasn’t come yet.”

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.