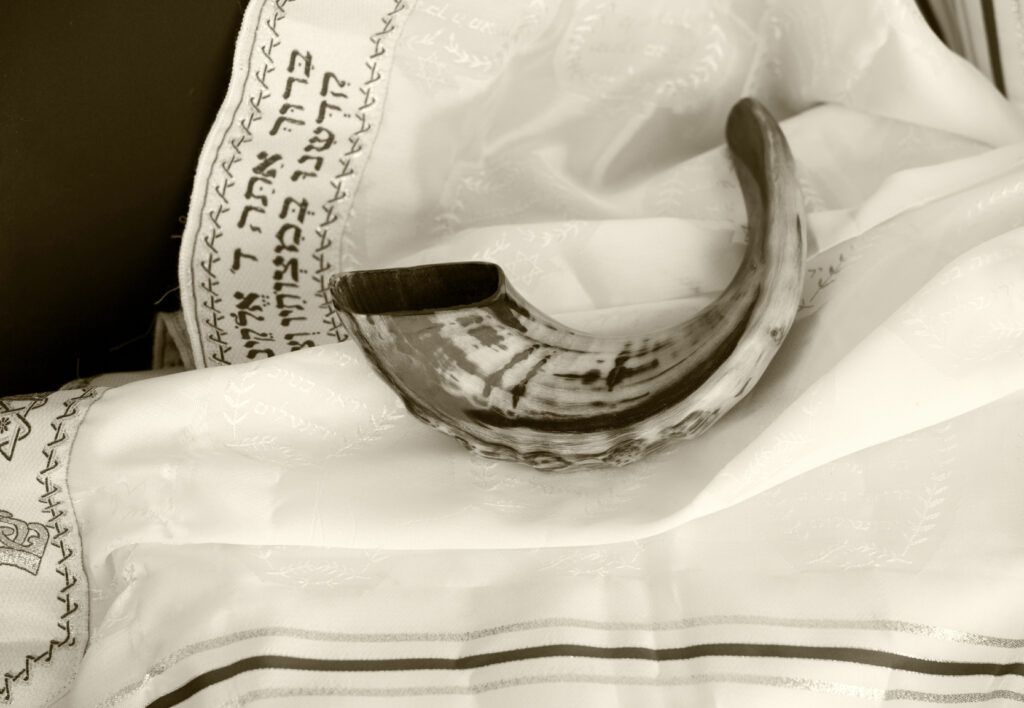

On Yom Kippur, my family, like most Jewish families, fasts. We forego physical nourishment to better focus on nourishing our souls.

Ten days into the start of a new Jewish year, the fast is meant to cleanse us, to prepare us to live better lives.

But as a little kid, all I could focus on were the growls coming from my stomach as I stood in synagogue. Even Temple Beth Torah’s drinking fountain was shut off, no relief to be had for my dry, itchy throat.

My mom missed coffee the most.

That morning cup of piping hot, any-brand-as-long-as-it’s-caffeinated beverage was her wake up drug of choice. Upon rising, she beat a direct path to the coffeemaker. If something delayed that first sip, something like an early morning phone call, a migraine would come on, swift and violent, the agony of first-stage caffeine withdrawal.

For her, Yom Kippur meant a headache.

After morning services, we returned home, and the fridge stayed closed, the faucets went unturned. Not so religious as to go without electricity, we would distract ourselves with television before returning for afternoon services. But my dad, younger sister and I could barely stand to see someone on the television biting into a sandwich.

Mom felt so ill, she isolated herself in her room, turned the lights low and buried her head in bed pillows. Often, she couldn’t even make it back to synagogue for the end of the holiday. The second the sun went down she made a cup of coffee, not waiting for the break fast meal we always attended at a family friend’s house.

Meals are the centerpiece of most Jewish holidays. But not Yom Kippur. Maybe that’s what made fasting on the day even more difficult. We went to the temple, we prayed, but the last part of the routine was missing. There was a hole and no bagels and lox to fill it.

One year, Mom finally had enough of the Yom Kippur headaches. She vowed to quit caffeinated coffee before the holiday. It wasn’t just for Yom Kippur, it was for her health. Something with that much power over her couldn’t be good.

Mom struggled. The migraines were bad. Advil and Tylenol didn’t help. The lights were dim in rooms of our house for weeks.

Then came Yom Kippur. For the first time, Mom actually looked…awake. During services, she stood and sat for prayers without a grimace on her face. When we returned home, she sat in the living room with all of us. She was back in temple for afternoon services. We arrived at our family friend’s house and Mom didn’t bolt straight for the coffee pot. She was cured. She was pain-free and happy.

Every year, on Yom Kippur, God sends a message: Now is the time to change. To quit bad habits, to make a fresh start. The fast helps us to listen, to pay attention. As my mom will attest, sometimes change is painful. But the gains? Good to the last drop.