In 1937, Billy Graham, 18, was attending a Bible camp run by the evangelist Bob Jones. Graham and a friend had been pulled in on an infraction, according to Graham’s biographer William Martin, and were duly chastised. Then Jones turned to Graham, his tone changing. “You have a voice that draws,” he observed. “Some people’s voices repel. God can use that voice of yours. He can use it mightily.”

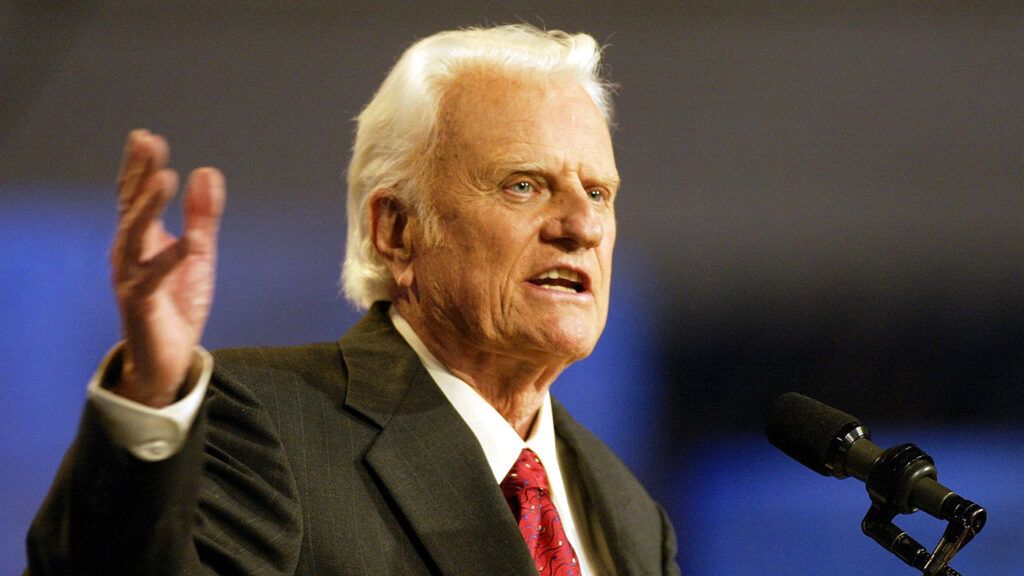

Jones was right. Graham, who died Feb. 21, 2018, at age 99, had a voice—and a style, an appearance, a personality, and an utter religious commitment—that in combination, were unmatched in the 20th century. And God used them mightily. Not just to bring souls to Christ, although Graham was undoubtedly one of the greatest preachers in the history of Christianity, one of the elite handful stretching back the Apostle Paul. But against what were initially high odds, he spent at least 50 years as one of the giants of American culture. Even nicknames like “the Protestant Pope” or even “America’s Pastor” fail to do Graham justice. He was, simply, the most influential American Christian figure of his age.

William Franklin Graham, Jr., was born on November 7, 1918, on his family’s successful dairy farm outside of Columbus, N.C. The Grahams were Presbyterians. At age 15, he accepted Christ as his Lord and savior; at 20 he was ordained into the ministry as a Southern Baptist. Much later, his wife would recall, “I’d never heard anybody pray like that.” After attending college and becoming a leader in a flashy new movement of young pulpiteers (thin ties, Day-Glo gabardine suits, green suede shoes), Graham attempted a solo tent revival in Los Angeles in 1949. One fateful morning a gaggle of national reporters and photographers met him as he arrived; the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst had released a terse all-points bulletin: “Puff Graham.” Writes Martin, “Billy became a truly national figure almost overnight.”

Graham had a perfect profile, piercing blue eyes and wavy blond hair. He was an outrageously magnetic preacher: pacing the stage like a restless panther; hands slashing down to carve out cadence, his pointed finger seemingly as concrete as Gibraltar; and that voice, declaring “The Bible says…”—all moving his listeners inexorably toward the climax: the exhortation to a decision for Christ. Right now.

Graham’s theology, writes historian Grant Wacker, never diverged that much from the basics: Biblical authority, human sinfulness, divine grace, heaven and hell, Christ’s anticipated return and the obligation to evangelize. But his version differed from that of fundamentalists like Jones in that it looked outward and forward rather than inward and backward. He preached the full laundry list of worldly woes, but his dominant note was the joy and triumph of a decision for Christ. In time he would say that belief in Christ was more important than the Bible.

This enraged some Christian elders. Graham famously replied “the one badge of discipleship is not orthodoxy but love.” Meanwhile, he took the larger world by storm. After Los Angeles came New York, followed by London. Over 55 years, The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association estimates he preached to “nearly 215 million people in more than 185 countries and territories,” and “led hundreds of thousands of individuals to make decisions” for Christ.

And that does not address his cultural reach. Graham’s long-running radio program, Hour of Decision, his various television shows, and innumerable non-preaching appearances and interviews impressed those who never attended a Crusade, making him one of the country’s most trusted names in mid-century, and into the next. In 2015, the Gallup organization listed him time as one of the year’s 10 most admired men in America. For the 59th time. At age 97. His last Crusade was a full decade earlier.

Graham avoided his vocation’s classic snares: There was never a whisper of sexual impropriety; in the one instance when his finances were questioned, he helped found the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability. Graham had what Martin calls an “abhorrence for disorder… and a trust in authority.” Thus he supported civil rights—courageously, given his core constituency—but when Martin Luther King was imprisoned in the Birmingham jail, Graham advised him publically to “put on the brakes a little.” He loved the company of Presidents, meeting each from Truman through Obama, He was especially close with Richard Nixon, and was deeply embarrassed by Watergate. Nevertheless he continued to extend praise just short of endorsement to Republican candidates, as when, at age 93, he told Mitt Romney in 2012, “I’ll do all I can to help you. And you can quote me on that.”

Many of Graham’s acts, like Jesus’ bit of yeast, yielded huge returns. Without Graham, it is impossible to imagine the seeker-friendly tone and suburban presence of the mega-church; without him, the shape of Christianity internationally would be entirely different. Without a beachside walk with Graham, George W. Bush would never have been born again. Without the Evangelicalism that Graham helped to foster, Bush would never have been elected—twice. And let us not forget those hundreds of thousands of decisions to come to Jesus.

Some of Graham’s gifts, like that voice that pulled, were non-transferable. But others, like a certain kind of optimism, flowed so naturally into the larger stream of American thought that it is almost impossible to tell where they imperceptibly shifted or accelerated certain currents. Wacker argues that Graham’s “achievement for all Americans… lay in the offer of a second chance.” This, of course, has been hard-wired into us since the Pilgrims. But like everything else in our nature, it is contradicted and counterbalanced by similarly powerful impulses. While Evangelicalism had always featured a born-again experience, the historian says, it had often incorporated a sharper “edge. You either are in or out, either on the bus or off the bus.” And Graham, he writes, played it differently: “The new birth served less as a way of telling some people that they were off the bus than a persuasive way of inviting ‘all aboard.’ Everyone.” These days, in Christianity and in the country at large, that is assumed far more widely than before the gangly young preacher arrived on the scene.

In 1952, after his first few years of national exposure, Billy Graham had a rare low-watt moment. “I’ve always thought my life would be a short one,” he told reporters. “I don’t think my ministry will be long. I think God allowed me to come for a moment and the moment will be over soon.”

His moment lasted another 66 years. Had he been right, think what we would have missed.