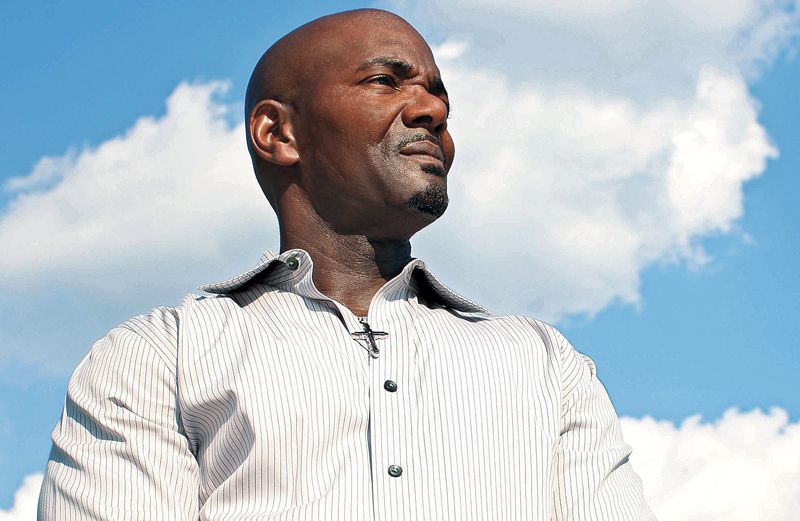

My name is Cornelius Dupree, and I am a sex offender. I paced the narrow aisle between the bunks in my cell, going over the words in my mind, trying to force them to my lips.

Those were the words I would have to say in front of the other men in the counseling program if I wanted to get out of prison. The words that would set me free.

Twenty-four years. That’s how long I’d been an inmate at the Coffield Unit, a maximum-security state prison in East Texas. I’d been convicted of robbing a couple at gunpoint when I was 19. I was serving a 75-year sentence.

Three times before, I’d come up for parole. Each time I had been turned down. I’d spent more of my life inside, behind bars, than I had outside, in the real world.

Now, at last, the state parole board was offering me a chance at freedom. But first I had to attend a sex-offender program and admit that I had raped the female victim.

I’d been charged with rape and robbery originally, and even though the rape charge had been dismissed, it was still in my file. If I admitted my guilt and expressed remorse, I would be released.

My fiancée, Selma, urged me to do it. So did my brother and sisters. I wanted to get out. I was tired of prison.

I wasn’t a kid anymore. I was middle-aged. I wanted to marry Selma. Get a decent job. Eat a home-cooked meal. Visit my mom’s grave. Meet my nieces and nephews. Do something good with what was left of my life.

There was one thing standing in my way. One huge thing: the truth. I hadn’t raped or robbed anyone. I was innocent.

I don’t mean that I was a squeaky-clean kid who spent all his time at church. I did go to church–I was baptized at age eight–but I can’t say I was mature in my faith or in my behavior.

In my teens I did the dumb things teenage guys in my Dallas neighborhood did back then–joyriding, drinking, smoking a little marijuana. Still, I had never been in really serious trouble.

That was why I wasn’t worried the night the cops picked me up, November 30, 1979. I was walking with Anthony Massingill, a guy I knew from the apartment complex where our families lived.

I hadn’t been planning to go out, but when he knocked on my door and asked if I wanted to go to a house party a few blocks away, I thought, Why not? I had put in a long day at work–I was a mechanic for a trailer company–and I was ready to have a little fun.

Halfway there we passed a couple of parked police cars. Officers jumped out and stopped and frisked us. I didn’t have anything on me, but they found a bag of marijuana and a gun on Massingill. I had no idea he was carrying either.

The cops put us in their car and took us downtown to the county jail for booking. I was upset but not worried. I hadn’t done anything wrong, after all. I thought it wouldn’t take long for the police to figure that out and let me go.

Massingill and I were brought to the courthouse next door to be arraigned. That was the first time I heard the charges against us. Aggravated rape and aggravated robbery. I almost jumped up and shouted, “What?!” I was shocked.

Marijuana possession and carrying a concealed weapon, I could’ve understood, considering what Massingill had on him. But rape and robbery…where did that come from?

The prosecutor told the judge that one week earlier, in the vicinity of where we’d been picked up, two men matching our description had carjacked a couple at gunpoint, robbing them and raping the woman. She had picked our pictures out of a photo lineup.

I was taken back to the county jail and put in a cell with seven other guys awaiting trial. I still wasn’t all that concerned. I’d watched Perry Mason, and I believed in the justice system. I believed that you were innocent until proven guilty. I believed that the truth would come out in court.

My mom, though, was worried. I could see it in her eyes, even though she tried to be strong. She talked about scraping together money to hire a good attorney for me.

“I don’t want you putting up your life savings for that,” I said. My parents weren’t well off. “They’re going to find out I’m the wrong guy and let me go.”

I spent months in the county lockup before my case finally went to trial. I was assigned an overworked public defender, who talked to me for maybe 20 minutes total. DNA testing wasn’t available back then, in 1980. No conclusions could be drawn from the physical evidence collected from the victim.

There was no other real evidence. The prosecution’s case was based on eyewitness identification, and that was hardly rock solid. I’d never seen either victim until they took the stand, but both testified that I’d robbed them.

The man, however, hadn’t been able to pick out my picture in the earlier photo lineup. The woman mistakenly identified a photo of Massingill as me even though I was right there in the courtroom for her to compare my face to the picture.

I thought I had a good chance of being acquitted. The jury came back after barely an hour. The foreman stood and read the verdict: “Guilty.”

The judge followed the jury’s recommendation and sentenced me to 75 years. I heard my mom gasp. I went numb. Everything sounded tinny and far away, like I was in the middle of a strange dream that had no connection to reality.

Reality set in awful quick in prison. At night I lay in my cell on my hard bunk, my mind running. Seventy-five years. Under Texas law, I had to serve at least a third of my sentence before I could be paroled.

That was 25 years. I would be 44 then. My mom and dad might not be alive by the time I got out. I might never get married or buy my own house or have a family. I might not make it out alive myself.

I’d believed in the justice system, and the system let me down. You know I didn’t commit those crimes! I railed at God. Why am I here? I felt betrayed.

My first years at Coffield, I walked around angry. A guy looked at me the wrong way, I’d get right in his face. “You got a problem with me?” I’d snarl. Maybe because I was smaller than a lot of the other inmates, maybe because I was young and foolish, I felt like I had to establish myself.

As I got into my thirties, I realized I had a choice: let bitterness swallow me, or use my time well. I had nothing but time, after all. I would do the best I could with it. I stayed out of trouble. I worked on the Coffield farm, picking vegetables and cotton, cutting grass.

When I wasn’t in the fields, I was in the prison law library, looking up cases that were similar to mine and citing them when I filed petitions to have my case reheard. Each time my appeals were denied.

That might have brought me down if I hadn’t met Selma. She was a corrections officer. She had such a godly way about her that I felt being in her presence made me a better person.

She didn’t want anything to do with me at first–she was planning to be a warden, and I was on the other side. But we started talking. I told her my story and she came to believe in me. She even quit her job so we could be together without any conflict of interest.

Selma’s strong faith inspired me to deepen my own relationship with God. I went to chapel, talked to God, tried to understand what his plan for me was. I prepared for the day I might finally get out.

I took classes–some, like African studies, to expand my mind; others, like meat cutting and air-conditioning and refrigeration mechanics, to expand my skills so that I could get a job after prison.

I can’t say my heart didn’t get heavy at times. When my mom’s health failed and I didn’t get a chance to say goodbye to her before she died. When DNA testing became readily available but the state turned down my petition to have it used in my case. When I came up for early parole–I’d earned time off my sentence for good behavior–only to be denied.

I knew my refusal to admit guilt was a big part of it, but I couldn’t bring myself to say I’d committed terrible crimes when I’d done nothing of the kind. It seemed like every door to freedom was closing for me.

That’s why when the parole board made its offer in 2004–the sex-offender program–I gave it serious consideration. “Just do it,” my brother said. “Don’t you think you’ve given up enough of your life? It’s time for you to come home.”

Selma said, “It’ll be okay. The people who love you know the truth. God knows the truth.”

I agreed to try the program. A counselor led the group and told us everything that was said in our meetings was confidential. The first few sessions, I just listened to the other inmates. And the more I heard, the more horrified I felt. What these guys admitted to doing, to their own children…it was sickening.

At the fourth session, the counselor told me that in order to complete the program, I would need to write down what I’d done and read it aloud to the group. If I didn’t participate, my parole would be denied.

“You’re going to have to stand up and say, ‘My name is Cornelius Dupree and I am a sex offender. This is what I did….’”

Now I paced my cell, mentally rehearsing those words. I tried to speak them aloud. I couldn’t do it. I couldn’t admit to something I didn’t do.

I got on my knees on the cold concrete floor. “Lord, if this door is closing for me, you must have a reason. You know the truth, and the truth matters. I trust you to release me when I’m ready.”

A shiver went through me and I got to my feet, feeling oddly unburdened.

My parole was denied. And because I wouldn’t participate in the sex-offender program, I was no longer considered a model prisoner. All the time I’d earned off my sentence was revoked.

That was the cost of holding on to the truth. But I don’t regret my decision. It’s what allowed me to hold on tighter to God.

Finally, on July 22, 2010, I was released on parole. I didn’t have to say I’d committed robbery or rape. By then I had served enough of my sentence–30 years–that by law, the state had to let me go.

I walked out the prison gate into Selma’s arms. We hugged and kissed and then we stood there in the parking lot and prayed, “Thank you, God, for this moment.” We got married right away.

The Innocence Project had been working on my case, and got permission for a forensics lab to compare my DNA with the evidence from the victim’s rape kit.

Eight days after my release, the results came back. They were conclusive: My DNA did not match either of the two male samples in evidence. I was innocent.

A Dallas judge overturned my conviction in January 2011, and the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals fully exonerated me two months later. It was gratifying to finally have people know the truth.

But really, my soul had been released of its burden years earlier, that day in my cell when I said, “Lord, I trust you,” the words that set me free.

Download your FREE ebook, True Inspirational Stories: 9 Real Life Stories of Hope & Faith