There was no mistaking the excitement in my father’s voice. “I saw an abandoned Studebaker in the woods where I grew up,” he told me over the phone. “It’s the same truck I rode in when I was a boy. I was hoping you could photograph it for me.”

I took a deep breath, hoping Dad wouldn’t sense my reluctance.

It had been more than a year since I’d had surgery to repair the detached retina in my left eye, but I still couldn’t see clearly. Things were fuzzy, indistinct, like what a nearsighted person sees without glasses. Not the sharp vision I needed to pursue my retirement dream of being an artistic photographer, the kind whose work gets published in photography magazines.

My passion was shooting high-definition, crystal-clear images that reveal the hidden beauty in everyday objects, the beauty I’d believed God wanted me to uncover. I knew both my parents wanted to encourage me, but no amount of encouragement was going to change the fact that even through my camera’s viewfinder, I couldn’t make out details well enough to focus and frame a shot properly. I hadn’t even wanted to pick up a camera lately.

Still, I didn’t have the heart to tell Dad no. “Sure, I’ll photograph the Studebaker,” I said. Maybe with a subject as big as a truck, I’d be able to pull off something. Was God giving me another chance? Or was he going to ask me to give up my dream?

My problems had started in 2005, with a retinal detachment in my right eye. Even after surgery, my vision in that eye was limited. Fortunately, with my “good” left eye, I could still do my job in the defense industry and take photos for fun. I retired in 2012, excited at last to dive into photography in a big way. My husband, Bill, was thrilled for me.

I’d loved taking pictures since my parents gave me my first camera, an Instamatic, at age 10. When I was 14, my friend Sandi taught me to how to be a photographer. She owned a 35mm camera, and even as a teenager she had photographed weddings and special events in our small Florida hometown.

She loaned me her Pentax and gave me suggestions on composition, settings and technique while we walked around the neighborhood. One day, she directed me to take photos of an old fence post.

“I’m not wasting film on that,” I said to her.

“Shoot it,” she said. “It’s my camera.”

Only when the prints came back was I able to see what Sandi had seen. The weathered grooves in the wood, the climbing ivy, even the bugs crawling over the surface… The tiniest details jumped out at me. Amazing! It gave me the shivers in a good way, like learning in Sunday school that God delighted in every detail of our lives.

“You’ve passed that fence post hundreds of times,” Sandi said. “Photography is about having an eye for things most people miss.”

In retirement, I finally had time to devote to photography again. I subscribed to photography magazines and admired the artistry and crispness of the images. “I want to have a photo published in one of those magazines someday,” I said to Bill.

“Go for it!” he said.

Bill, my mom and I went on a 200-mile trek around the small towns of central Florida, where we’d grown up. Bill is a general contractor who’s great at noticing interesting details in the built environment. I spent days capturing images of handmade brick roads near Espanola, sand pines and palmettos in the Ocala National Forest, the orange groves heavy with fruit, the car ferry at the St. John’s River.

Sandi died in 2014. I spoke at her memorial service about how she’d inspired me to look for the beauty in the ordinary. Her death reminded me that life is precious and made me even more motivated in my photography.

Less than a year later, the retina in my left eye detached and I had emergency surgery. I was terrified that I would end up near blind. I begged God to save my vision.

When the eye patch came off and I could see, Bill and my parents rejoiced with me. But as several months passed and the fuzziness in my vision, both near and far, didn’t clear up, the joy leaked out of me. Mom reminded me the doctor had said healing could take up to six months.

I couldn’t wait that long. I had to try using my camera. Bill took me to one of my favorite spots, a beach on Lake Minneola. The late-afternoon sun was soft, highlighting the planks of the old dock. I tried to compensate for my blurry vision by adjusting my camera’s diopter. But when I uploaded the photos to my computer, I had to enlarge them 70 percent just to make out what I had shot. The images were a letdown—not crisp at all.

The same thing happened on subsequent shoots. I’d read in my magazines about editing software, how it could be used to deepen or lighten colors, remove shadows, change almost anything about a photo. Surely there was a way to make the images razor sharp. To give them exquisite detail that jumped off the pages. I’d used computers most of my career. I figured I could teach myself how to use the software.

It was harder than I’d imagined. After watching hours of instructional videos, I could do a passable job of “painting” a photo a new color, but sharpening the image? I wasn’t happy with anything I tried.

One day, I decided to work on a photo I’d shot years earlier of an antique typewriter. I hadn’t used a flash, and the lighting was poor. On my computer, I increased the brightness and added an oil paint effect.

“That’s so cool,” Bill said. “It looks like it’s on fire.”

“But it’s not photography!” I said, unable to contain my frustration. “I want to shoot photos that are sharp, like I used to. To document God’s hand at work.” I’d passed the six-month post-surgical mark by then, and my doctor had said my visual acuity was the best it was going to get.

Maybe God was telling me to be thankful for the healing I’d been granted and to move on. Maybe it was time for me to accept that my dream was dead. I didn’t touch the photo-editing program for months. My camera sat unused in its bag. Then came Dad’s call about the Studebaker.

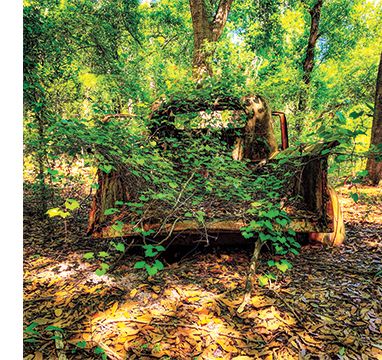

The rusted-out truck, its oversize tire shields mired in mud, sat far back in the woods, covered in vines. I stomped around the tall swampy grass, swatting mosquitos, shooting from every angle imaginable. The deep shade made the lighting tricky, but it felt good to be doing something creative again.

I went home and reviewed the shoot on my computer. My heart sank. I’d taken 300 photos, and every single one had problems. Strange shadows. Images out of focus. Awkward angles. I’d made a total mess of it. That’s it, I thought. I’m finished.

When I told Bill about my disappointing results, he said, “What if you tried something like what you did with that typewriter photo? I bet that would look amazing!”

Bill just didn’t get it. I pointed to my stack of photography magazines. “I want to shoot crisp, clear photos, like the ones in those,” I said. “Out of 300 shots, I ought to be able to get one right.”

Bill gazed at me for a long moment. “Why are you trying to make your work look like someone else’s?” he said. “God has given you a chance to do something original, to express your creativity. Reframe your limitations. Look at this in a different light.”

Here was a message I could understand. Landscape photographers return to the same location numerous times because variations in light can give an image a completely different look and feel. There are countless ways to capture a single subject. Why had I thought there was only one way for me to be a photographer?

I went back to learning editing software, experimenting with different effects until it became second nature. Bill suggested I print the typewriter photo on metal instead of canvas, adding a whole new layer of expression to it. That photo won second place in a state competition.

I chose the photo of the Studebaker I liked most and enhanced it, adding more color, vibrancy and texture, playing with the light to bring out the green in the vines, while allowing the truck itself to stay in softer focus. The effect was dreamlike. Definitely one of a kind. And beautiful in a way I would never have seen or appreciated before. Dad loved it. It seemed as if everyone who saw it knew of another old car for me to photograph. Bill and I started going on photo treks again, working as a team. I’ve got the creative vision; Bill sees details I miss.

My photos have been displayed in galleries, prestigious art festivals, municipal buildings, even the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts. I’ve won competitions and seen my work published in magazines. More recognition than I’d ever expected.

For Father’s Day, I presented my dad with a photo of the Studebaker printed on wood. At the bottom of the image is a verse from Ephesians: “For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus unto good works, which God hath before ordained that we should walk in them.” One of my favorite Scriptures because it explains how my dream has been fulfilled and then some. My vision may be limited, but God’s never is.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.