Climbers gathered around me inside our mess tent, 15,000 feet up Mount Kilimanjaro, a dormant volcano and Africa’s highest peak. I saw the doubt and worry in their eyes, 13 men and women diagnosed with either multiple sclerosis or Parkinson’s disease.

I heard them straining just to get a full breath. It was going to be a long night.

“This isn’t about the mountain,” I said, glancing at Dad for encouragement. “It’s about believing you can still achieve your dreams.”

I hoped they’d find strength in my words, knowing I’d gone before them. But I also knew what lay ahead. The final 4,000 feet to the summit were a punishing, dark, oxygen-deprived gauntlet. What could I say to them that would make a difference?

I looked to Nan, hoping I was reaching her. A 65-year-old retired anthropologist, she’d been diagnosed with Parkinson’s four years earlier. Since then she’d ridden a bike across Iowa. Kilimanjaro, though, was a challenge beyond that. She smiled, but it seemed forced.

Beside her was Ines, a 24-year-old psychologist from Spain, diagnosed with MS when she was 17. Every morning she awoke afraid her paralysis had returned.

Then there was Nathan, 54, a mill worker. His Parkinson’s was so severe he’d had two stimulators implanted in his brain to regulate his tremors. Even that could only do so much. I admired his determination, but still…

I knew very well how high the stakes were for all of them. They’d come seeking the liberation from fear I’d held out to them. I prayed it would happen for them as it had for me. I wasn’t here just as a team leader. I too had MS.

I remembered like it was yesterday waking up, half of my body numb. I was terrified I’d spend the rest of my life in a wheelchair. But 10 years later, in 2009, I stood atop Mount Everest transformed—physically, spiritually, mentally—the first person with MS to reach the roof of the world.

Everything changed after that. Everyone, it seemed, wanted to hear my story. That’s how I’d gotten connected with Nan, Ines and Nathan, all the climbers—speaking to foundations, churches, support groups, civic clubs and charities around the world.

But I didn’t want people to look at what I’d accomplished as an unattainable goal. I wanted to give them their own mountaintop experience.

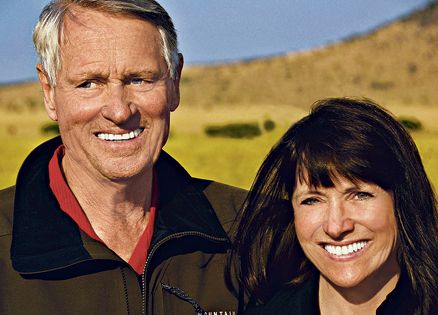

Now here we were after climbing for five days, our shared dream only seven hours away. I’d chosen partners for each of them, people whose job was emotional support. That’s why Dad, at 79, was here. It was a chance for our climbing dream to come full circle, and to again support each other every step of the way.

There was one more thing to do before we broke camp. I reached into my backpack and pulled out 27 handwritten notes. I’d written them at night in my tent, letters of encouragement for the climbers to carry with them to the top.

I went to Nan first, hugged her and handed her the envelope. Inside I had written: You are a beautiful woman inside and out. Never forget your power. “You’re going to do great,” I whispered. She nodded nervously. Her partner, her husband, squeezed her gloved hand.

Slowly I worked my way around the circle. With luck the first of our three climbing groups would make it to the summit by daybreak, about 5:00 A.M., followed shortly thereafter by the rest. But plenty of things could go wrong.

Every year a handful of climbers die on Kilimanjaro, mostly from altitude sickness. A note didn’t seem like enough.

Dad and I shouldered our packs, filled with energy gel, bottles of electrolytes, and hand and foot warmers. We pulled on our gloves and went outside with the others into the dark. I flipped on my headlamp. I could see the light from Dad’s lamp just ahead of me.

The fastest climbers went in the first group. Remarkably, Nathan was in that group. Dad and I joined Nan and her husband pulling up the rear in group three. Slow and steady was the best pace for us, plus I wanted to watch the others’ progress.

I put my right hiking pole in the scree, the loose, slippery rock that covered the top third of the volcano, and planted a boot behind it. My foot slipped and I shifted my weight to get my balance. I looked down, willing my legs forward. It was critical not to stop more than absolutely necessary.

Soon my lungs struggled for air, each breath capturing only half the oxygen available at sea level. I couldn’t talk to Dad, but it comforted me to follow in his footsteps. As long as Dad was in front of me, leading, all would be well. It had been that way my whole life. Dad had inexhaustible faith in me and in God.

I remembered how we climbed here 18 years before, the first peak for us. That view from the top, the African plains stretching far off to the horizon, was mind-blowing. “I don’t want to quit,” I told Dad. “I want to do the Seven Summits—climb the highest peaks on every continent.”

“I know you can do it,” Dad said. He’d never stopped believing in me, even after I was diagnosed with MS. Six months later, at the turn of the millennium, he was there beside me on Mount Aconcagua in Argentina. And he’d been with me in spirit for the other five.

I called him from the top of Mount Everest by satellite phone. “You’re stronger than you know,” he told me that day. “Don’t ever lose faith.”

It was still pitch dark when our group pulled up for a quick rest and shots of energy gel. I could see the headlights of other climbers snaking up the trail, like a parade of fireflies. “It seems like I can almost touch the stars,” Nan said. “It’s beautiful.”

I glanced at Dad. He was quiet, but looked okay. His eyes twinkled when they met mine. “We’d better get going,” I said. “There’s still a long way to go.”

Through the night, hour after hour, we climbed. The space between the climbers was growing; we were too far apart to take breaks together. Dad’s pace was slowing. We had to keep moving—that was the key.

I could barely make out the outline of the summit, silhouetted by the sun just beginning its ascent. Then suddenly Dad stopped. I closed the gap between us as quickly as I could.

“I have to turn back,” he said. “My legs feel so weak I can barely lift them.” His breathing was tortured.

“I’ll come with you,” I said.

“No,” he said, his voice a whisper. “You have people depending on you.”

I looked up the trail beyond Dad. I could barely make out the shape of a woman, 100 yards ahead—Nan. It looked as if she’d stopped as well. What if everyone was hitting the wall at once? I desperately wanted to go down with Dad, but I needed to support my climbers.

“Don’t worry, Lori,” Dad said between gulps of air. “I’ll be with you in spirit.” I watched as he shuffled away with the aid of a guide and a porter, sensing that he was praying already, just as he’d always prayed for me when I climbed.

I turned toward Nan. I was alone. It would take me at least an hour to catch up to her. What help could I possibly be to her or any of the climbers? My heart went out to them. Give them strength, I pleaded.

I took a step and slipped, catching myself with my poles. Slow was the only speed I could go. One, two, three… I counted off paces by fives, urging my legs not to quit. Without Dad in front, the path seemed darker, my headlamp barely able to cut through the gloom.

I was too tired to do anything but watch my boots plod through the scree. I tried to block out everything else around me—the cold, the pain spreading through my legs, Dad’s absence. One, two, three…

Finally I looked up. The sky was a beautiful pinkish blue, the hours of darkness gone. Heaven itself seemed to say, You can do this. You’re not alone. There was Nan, only 50 feet away, Ines ahead of her. They were walking, relentlessly, at a snail’s pace, but it was just enough, the top now only an hour away.

We reached the rim of the volcano. The vast crater stretched before us, too massive to see across. The ground began to level out. We picked up the pace.

I saw people coming toward us, at first just ants in the distance, but as they grew closer I saw Nathan leading the pack, striding confidently. The first group, returning from the summit! “That was awesome!” he said.

We exchanged hugs and continued on. Our group was next. We went up a slight rise, and then we were there—a wooden sign confirming what was obvious to our eyes. Above us was sky. Below us was an endless panorama, the fabled African plains, shades of rich browns, yellows and greens, breathtaking in their sweep.

The circle of life. “I can’t believe it,” Nan said, wrapping an arm around Ines’s shoulder. “We really did it.”

“You guys are amazing,” I said.

Ines looked at me, her eyes full of wonder. “Thank you,” she said. “But without you, Lori, none of us would even be here. You believed in us. That’s what made all the difference.”

It wasn’t just me, I wanted to say. It was the millions of people across the earth who struggle bravely every day with debilitating conditions, for whom walking across a room can be as daunting as climbing the highest peak in Africa. It was their hopes, their strength, their unyielding faith that we all shared.

I scanned the rocky face of the mountain. Dad was down there somewhere, slowly making his way to base camp, praying for our safety.

But all he had taught me was with me: love, faith, encouragement, and knowing that the steepest obstacles can be conquered when we work together and trust together, when we replace fear with belief.

View images from Lori's trip up Kilimanjaro!

Download your FREE ebook, Rediscover the Power of Positive Thinking, with Norman Vincent Peale