“It looks like a perfect spring day to go fishing,” Mama said when I answered the phone. I listened close to gauge whether or not she sounded sober. So far, so good. “Supposed to get in the seventies today.”

“Actually, Scott and I were planning on trying our luck down by the river this evening.”

“Mind if I come along?” The question made my fingers tighten around the phone. Why had I even mentioned it? If I let my guard down for one second, things got complicated with her.

Nothing about Mama—or her drinking—was simple. Trying to have a relationship with her was like dancing with dynamite. But how could I shut my aging mother out of my life and refuse to let her spend time with her grandson? And what was I suppose to say to her now that I’d admitted we were going fishing? Mama loved to fish.

“Are you still there?” Mama asked.

“No beer, Mama,” I said, embarrassed to have to say the words. Again. But after only six months back home following my divorce, and several bad experiences, I had set that one boundary. If she wanted to be around Scott, there would be no drinking.

“Of course not,” Mama said, as if she were appalled at the very idea. I felt the conflicting emotions settle in.

“We’ll go down to the river about six,” I said. “The catfish bite better in the evening.”

“See you then.” Mama’s voice escalated with excitement. “Nothing more fun than being on the river in Oklahoma in the springtime. Seeing the Canadian geese, watching the fish jump.”

Mama had that magical side to her. She’d always had the ability to grab life and live it to the fullest… when she was sober. I hung up the phone and made a quick decision not to tell my five-year-old son that his grandmother was coming. It was too difficult to explain why Grandma didn’t show up when we were expecting her.

Later that afternoon Scott helped me dig for worms and gather up the fishing tackle. I fought the emotions that lingered—the stress, the guilt, the confusion. How many chances did Mama deserve? Was I right to trust her around my son? I took a break to sit still and pray: Lord, help me. Please show me the way when it comes to my mother.

It was a prayer I’d repeated a thousand times since childhood. Mama’s problems with alcohol had left a wake of destruction that could never really be healed, but I had kept trying. The minute my two brothers turned 17, they had fled the state. My older sister, who still lived nearby, had recently shut Mama out of her life for good. Maybe my siblings were smarter than me. Maybe all the turmoil and frustration of dealing with my mother would only lead to more heartache in the end. But I couldn’t dismiss Mama’s joyful, loving side. Surely that was worth something.

I got up and went to the porch. Scott played in the yard with our dog, Twain. I tried to untangle a fishing pole. “Forgive seventy times seven,” I whispered. After going through my divorce, I had become less judgmental. But even Jesus lost patience with the money changers. When was enough, enough?

“Look, it’s grandma Johnnie!” Scott’s shrill voice cut through the evening. We grabbed our gear and started off. My son loved his grandma, in spite of her broken promises and occasional strange behavior.

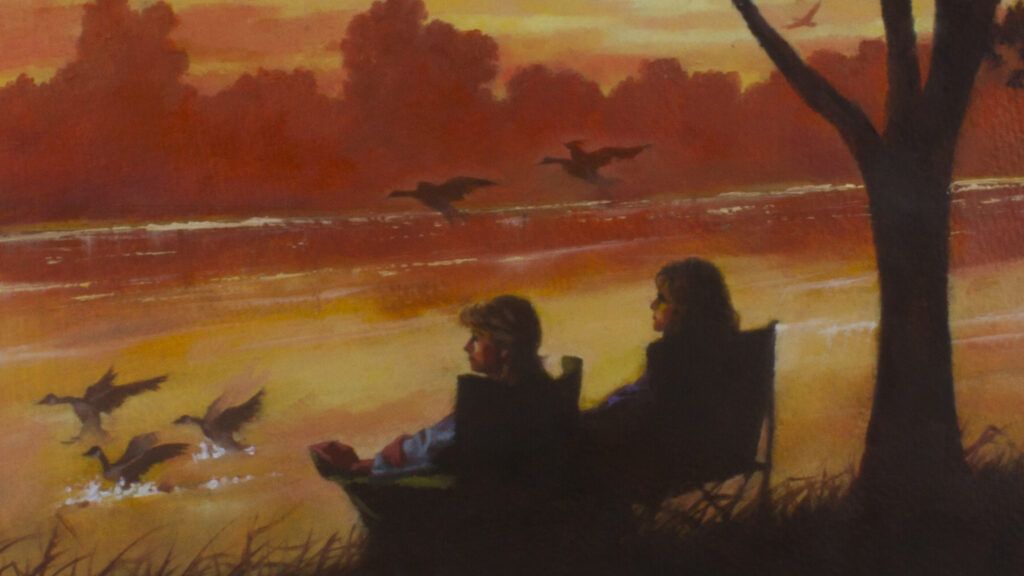

An hour later, as the sun set on the Arkansas River, Mama and I sat in silence, watching a flock of Canadian geese wade in a shallow tributary and dip their heads into the water after small fish. Scott tossed a stick for Twain. Neither one ever tired of playing fetch. “He’s a happy boy,” Mama said.

I didn’t take solace in her compliment. Instead I flashed back to my own childhood. Mama had left our farm, left our family, left us with our dad when I was close to Scott’s age. I forced the bitter memory out of my head. Please show me the way.

The lyrics to a song I’d just learned came to mind, and I heard myself try a couple of lines aloud: “If I had the wings of an angel, over these prison walls I would fly.”

“Where in the world did you learn that song?” Mama blurted out. Her tone of alarm caused the geese across the way to fly up in a chaos of honking and flapping wings.

I turned toward my mother. “I just heard it somewhere and liked it.”

Mama stared at me with a perplexed look. “That was my father’s favorite song. I don’t remember much about him, but your singing opened a window to the past.” She looked out on the river, remembering, I guessed. Remembering what was lost on me, considering how little I knew about her past. Only that she had lost her dad at an early age, and she’d been shuffled around to friends and relatives while her mother worked to support five kids. We had no connection to any of Mama’s people, and I wasn’t sure if she did.

As the sun faded further into the western sky, fireflies began to blink along the far bank of the Arkansas River. “Guess we better call it a day,” I said.

“Guess so,” Mama said, slowly getting up from the riverbank. “No luck on this day. But they’ll be biting next time.”

Scott bounded down the path back toward the house with Twain jumping and barking around his heels. I watched my mother walk slowly in front of me with her fishing pole and can of worms. She seemed somehow smaller. A flood of empathy rose up in me. There was no way to know what she had suffered in her childhood, and no reason to think she’d share it now. But maybe, in time…

The song came back to my lips and I began to hum as I walked. Perhaps there were other songs or connections that would help her open up. “If I had the wings of an angel, over these prison walls I would fly…”

Mama stopped, turned and smiled. “Thanks for letting me come,” she said.

I didn’t have answers for Mama’s addiction to alcohol, and I sure didn’t know what to expect in the future. I didn’t have the wings of an angel, but I had the security of knowing that God was guiding me through the darkness, showing me the way.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Angels on Earth magazine.