Our nation does a lot to honor military veterans. But one group of veterans often gets overlooked.

Women.

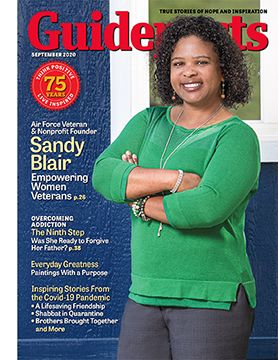

2020 issue of Guideposts

I should know. I’m a woman and an Air Force veteran. I served for 12 years, until a medical discharge prematurely ended my military career.

Like many veterans, I struggled to gain a foothold as a civilian. I couldn’t find work. After years of structure and camaraderie in the military, I felt alone and adrift. I endured a period of homelessness and sank deeper into despair.

Women veterans face unique challenges. They are often single parents, as I was. When they leave military service, they frequently take on caregiving roles, as I did, nursing my father after he suffered a stroke. They may encounter discrimination. I was told I was overqualified so many times in my job search, I wondered if race or gender wasn’t the real issue.

My immigrant parents taught me the value of self-sufficiency and hard work. Those values cut both ways. They were a huge help in the military, where I reveled in the discipline and opportunities for advancement. When I struggled after my discharge, I didn’t know how to ask for help. Like many veterans, I thought I should be able to take care of myself.

It was ultimately God who taught me that no one is truly self-sufficient. We all need God’s love. And we all need one another.

That’s the vision that powers the work I do now. I run a nonprofit in central Califlornia called Operation WEBS: Women Empowered Build Strong. Our mission is to help women veterans by inviting them into a community of love and mutual support.

We started small, with what I call a “stability home” in a town near California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base. It’s a modest four-bedroom residence where women veterans help one another get established and launch into fulfilling lives.

We’re in the process of expanding to a small ranch outside the town. We plan to build several “tiny homes” on wheels, snug single-room residences that can be grouped together into a supportive community.

It’s the kind of place I wish I could have found in the bad old days, when I felt so alone, unable to move forward. Now I give thanks for those days. My struggles back then help me understand what women veterans need now. God turned what appeared to be a dead end into a path toward love and service.

Like my parents, I am an immigrant. My mom and dad, seeking greater opportunity, moved my five siblings and me from Jamaica to New Jersey when I was nine years old. My parents were people of faith and raised us kids that way. I remember my grandmother back in Jamaica giving away the fruit from her trees because she believed God called her to be generous. “The Lord will provide,” she said when I asked what would happen if she ran out of fruit.

My father was a machinist. My mother worked at a hospital and cleaned houses. Both of them were proud and fiercely independent. Dad’s often-repeated motto was: “You get up, you go to work every day and you don’t ask for help.”

Those values drew me to the military. Dad had taught me how to use tools, and at first I wanted to become an Air Force mechanic. Dad said that was no job for a woman. He advised me to switch to a medical unit, where I trained to become a dental assistant.

I did that work for nearly a decade. After 9/11, I was reassigned to augment military police forces serving overseas.

I planned to be career military. But during my time in service, I developed a powerful allergy to latex. No idea how it happened. The bottom line was, I was unable to wear the protective gear required in certain training and combat situations.

I requested a reassignment, but the training I needed to switch roles wasn’t immediately available. I was discharged in 2005.

Along the way I had married, divorced and had two kids. Suddenly I found myself a single mother in the Florida panhandle. My last assignment had been at Florida’s Tyndall Air Force Base.

I applied for dental hygienist jobs in the area, but I kept hearing the same thing: “Overqualified.” Or I was told my military training didn’t line up with state licensing requirements. I offered to get the necessary certifications, but I was always told no.

I wondered whether race was a factor. I expanded my job search to Orlando, where a close friend lived. Still no luck. I applied for veterans’ benefits, but the paperwork took forever to process.

I was running out of money. Finally the kids and I had to move in with my best friend. By that point, I was applying for any job I could find, including fast food. I had been employed every day of my life since high school. Having no job was such a comedown. I hated imposing on my friend.

My parents and the military had taught me the same things: discipline, hard work, inner strength. Asking for help wasn’t just humiliating. It felt wrong somehow.

One day, I was out looking for work. Would the kids be better off without me? I wondered. I felt as if I were dragging them down. I was a burden on my friend. A failure.

I thought about how I might end my life. I left God out of this conversation. I was already mad at him. For the first 32 years of my life, I had done everything I was supposed to do. And now I was living like this? What kind of God would allow that? The Lord hadn’t provided after all. Maybe he wouldn’t even care if I killed myself.

My cell phone rang. It was Mom. “Sandy, your father has had a stroke. He is in the ICU. I need you. Can you come home?”

My parents had moved to Georgia. Mom worked at a hospital in Atlanta, and Dad continued as a machinist. He’d had the stroke at work. He was 62.

That call was a God thing. It saved my life. I scooped up the kids and moved in with my parents so I could take care of Dad while Mom was at her job. It was almost unbearable at first, seeing my strong, self-sufficient father so helpless, but I gradually came to value caring for him. Being tender toward this man who had worked so hard for so long.

I went to school to get certified in residential construction, figuring I could find work building houses. Then the 2008 financial crash wiped out the homebuilding market.

Shortly after, a postcard arrived at my parents’ house announcing openings at the DeKalb County Police Department, near Atlanta. Another God thing. I had no idea where that postcard came from, but I had experience in police work.

I passed the departmental exam and for nearly five years served as a DeKalb County police officer. I started on night patrol, leaving the days free to care for Dad. I saw every social problem you can imagine. Driving around the city at night, I had conversations with God about how to help the people I encountered.

My son graduated high school and said he wanted to attend college in California. One of my sisters lived there, in Orcutt, a working-class town near Santa Maria in central California. The kids and I moved in with her. I found work as a real estate agent and an administrative assistant at a community college. Once we were settled, we brought Mom and Dad to live with us.

The kids went off to college. Was I finally in a place to do something about those nighttime conversations I’d had with God while on patrol in Atlanta?

Santa Maria is a world away from Atlanta, but there are a lot of veterans in the area because of the nearby Air Force base and it’s a culture that values military service.

I thought about what I could have used during my time of struggle. A place to live. Help getting veterans’ services. Friendship and support from other people like me.

An idea began to take shape, especially after I learned about an organization called Operation Tiny Home, which builds tiny one-room homes on wheels to help create safe communities for veterans across the nation. What if I built a community of such houses for women veterans?

My sister and I pooled our resources and found a small ranch property just outside the city limits of Santa Maria. I pictured a small group of women veterans living in tiny houses and helping maintain a community garden while getting their lives back on track.

We moved our family to the ranch and converted our house in Orcutt into a stability home. We’re now in the process of raising money to build the tiny house community on the ranch.

Working with the county government, veteran resources and local nonprofit organizations, we began getting referrals of women veterans who needed a supportive place to live. We welcomed our first resident to the Orcutt stability home last year. After living in a local shelter for two years, she was thrilled to have her own room and regular access to a hot bath instead of a community shower.

Since then we have housed a total of seven women ranging in age from 33 to 70. These women have served their country, but they have struggled with military trauma, unemployment, abuse, poverty, addiction and homelessness.

We connect them with veterans’ service organizations and help them find jobs and permanent housing, such as their own apartment. Most of all, we provide them with a safe and supportive environment where they can live with other women veterans who share their military background and understand their difficulties. Everyone helps everyone else reach their goals.

The coronavirus pandemic has disrupted our plans, but I remain committed to our long-term vision. Finances are a struggle for any young nonprofit. It’s been a strain making mortgage payments on both the house and the ranch. I admit, I’m more skilled working with my hands than I am working with money. Asking for contributions goes against my deeply ingrained upbringing.

But I’m learning. When I think back to that difficult time after my discharge from the military, I realize that the hardest part for me was admitting I needed help.

And yet everyone needs help. Especially veterans. Especially women veterans.

I feel blessed to have learned that. To have lived it. And, at last, to be able to do something about it, just like I talked to God about.

Learn more about Sandy Blair’s housing assistance service, Operation WEBS (Women Empowered Build Strong).

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.