Only one thing was missing that Christmas, but it was all that mattered.

My three grown children, their spouses and their kids crowded around the tree in the family room, opening presents. Laughter, conversation and the occasional shriek of delight from a grandchild filled the room. Soon the floor was strewn with wrapping paper. Just like Christmases past.

From my spot in the middle of the sofa, I gazed at my family. I was surrounded by people I loved, people who loved me. But without Shirley, my wife of 58 years, I felt empty. Joyless. She’d been my everything.

There was part of me that couldn’t wait until everyone left and I was alone. Alone with my grief and my memories. It had been seven months since I’d lost Shirley, seven lonely months. I’d tried to throw myself into my work, my writing and speaking, telling everyone—including myself—that I was okay, praying that God would make it so.

Come Christmas, sadness hit me like a shock wave. Feelings I didn’t know what to do with, how to even put into words. Shirley would have been able to help, to draw it out of me. There was no one I’d ever been able to talk to so easily. She had been the one person in my life that I could be completely open and honest with, totally vulnerable with.

I didn’t have that kind of relationship with anyone else. Not my closest friends, not my children. I didn’t want to burden them. Instead I withdrew into myself.

Finally there were no more presents left to open except for one. The room got quiet. My granddaughter Layla, a budding artist, handed me a slim, beautifully wrapped gift. The littlest grandchildren crowded around to see what could be inside.

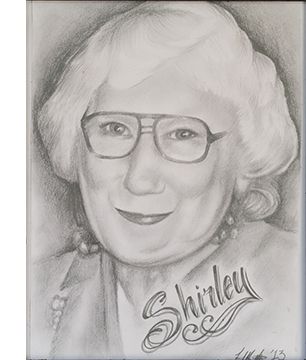

I tore open the paper. There, staring back at me, was Shirley. Layla had taken one of my favorite photos of her grandmother and done a line drawing. It was exquisite, but seeing it made me miss Shirley even more. “Thanks,” I murmured. I couldn’t think of anything else to say. I hugged Layla and awkwardly met the expectant faces of my family. Finally my daughter Cecile announced it was time for dinner.

I picked at the sweet potato soufflé and corn bread dressing my children had prepared. Shirley’s sweet potato soufflé was a favorite of mine, a dish she made at least once a month for me. Now it just didn’t taste the same. I couldn’t take it anymore. I excused myself and slipped out of the house, desperate to be alone.

My feet automatically headed for a park about a mile away. How many times had Shirley and I taken this route? Walking had been one of our cherished rituals, a chance to talk about our days and our feelings.

Shirley had grown up in a family that was matter-of-fact and didn’t delve into emotions. Sharing her feelings was completely new…and difficult. I was more open, more expressive. I was a minister and a writer. Words came easily. But there was a chapter from my past I’d kept buried for years. I’d been abused as a child.

I couldn’t bring myself to talk to anyone about the shame, the anger, I felt. Yet Shirley had that way about her, a look in her crystal-blue eyes, that made me feel safe and accepted. I didn’t want there to be any secrets between us.

“There’s something I need to tell you,” I told her one day. “But I’m worried it will change how you feel about me.”

“Impossible,” she said. “You can tell me anything.”

Once I began, the words poured out of me. Memories and emotional torment I thought I’d never be able to share with anyone. I saw her sadness and anger at what I’d suffered. Most of all, I felt her love, a love without demands or reservations. That allowed me to find healing, to truly know God’s love.

We had a routine of talking before dinner about everything that had happened that day, the highlights, the challenges and the mundane. Shirley would tell of a neighbor moving away or our baby’s first steps. Just the facts, at first.

“How does that make you feel?” I’d ask. I’d talk about a new book I wasn’t sure about. My worries in the early years of our marriage, when money was tight. She’d been there for me through it all: 14 years of pastoring, six years of mission work in Kenya, the nearly 140 books I’d written or cowritten.

Our talks brought us closer emotionally and spiritually. We spoke often about faith, the ways we saw God working in our lives. Even as our family grew and our lives got busier, we’d made time to talk. How I missed those conversations!

Shirley suffered from terrible spinal stenosis as well as kidney issues for the last seven years of her life. During her last six months, the pain was constant. The doctor said increasing her pain medication would cause further kidney damage. So she endured.

With the help of our children, I’d devoted myself to caring for her. “I don’t want you to be alone,” she told me. “Promise me you’ll remarry.”

“I have the kids,” I said. “I’ll be fine. Don’t worry about me.”

But she wouldn’t let it go. She even pushed our older daughter, Wandalyn, to find someone for me.

On our last day together, Shirley said, “I’ve not been good about telling you how much your writing has meant to me. Your words touch my heart because you try to live them.”

“I love you,” I said. “Always.”

Just hours later, she was gone. Now, walking in the park on Christmas, I thought about how insistent Shirley had been that I remarry. “You knew I’d be hurting, that I’d need someone to share my feelings with, didn’t you?” I said. Even at the end, her thoughts were on me.

I slumped on a bench, my arms hugging my torso, and rocked back and forth. “Lord, I’m so lonely without Shirley,” I said. “So lost.” The words came out more as moans, swept away by the wind rustling through the barren branches of the tree.

I looked up at the gray sky. I saw the image of a figure, his arms wrapped around a woman, like a huge cloak, so that only the woman’s face was exposed. It was Shirley! Enveloped in God’s loving arms. She looked joyous, free of all pain. “I’m so happy for you,” I said. And I was, even if it meant not having her here with me. She was with God. How could I not take joy in that?

I watched the vision melt into the clouds, and I knew what the message was. God wasn’t magically going to sweep away my grief. But he didn’t want me to isolate myself, to bear my pain alone any more than he’d wanted Shirley to bear hers.

There was only one path forward. I had to be honest with myself, with my family and friends, about my feelings. I needed to acknowledge the pain and not be afraid to feel it, to express my emotions. Just as I had all those years ago in opening up to Shirley.

It was time to get back to the house, to my family. My steps were lighter going home.

I walked inside. Everyone was in the family room again, the lights on the tree still aglow, carols playing softly in the background. Christmas in all its splendor. No one demanded to know where I’d been. They just made room on the sofa for me.

“I went out for a walk,” I said. I paused to gather myself before going on. “I miss your mother terribly. It’s important that I tell you that.”

One by one, everyone talked about how much Shirley had meant to them, even the youngest grandkids. Memories and feelings we hadn’t taken the time to share as a family since the funeral. “Remember, Dad, we loved her too,” said my son, John Mark.

He, Wandalyn and Cecile reminisced about one Christmas when we lived in Kenya, a time when money was tight.

“Mom made sure we got the presents we wanted,” John Mark said.

Cecile said she’d overheard Shirley and me talking about how we wouldn’t give each other gifts that year, so the kids could have nicer presents, such as the children’s sewing machine she’d asked for.

I’d forgotten the details of that Christmas. But now, looking back, what stood out to me was not the presents but the love. That was Shirley’s doing too.

I could still feel that love, and I was at peace with her passing. I looked up at the mantel, where someone had set my granddaughter’s drawing of Shirley so she would always be with us.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.