Whenever people ask me what I remember most clearly about that night on the sinking Titanic, I am hard put to choose. And yet, sometimes I think it just might be the stillness—the stillness and the hymn we sang to blot it out.

It has always struck me as ironic that on the night the iceberg ripped that long gash in our starboard hull—April 14, 1912—the sea itself was serene. The air was frosty cold, but there was no wind and the sky was crowded with stars, all brazenly large.

It was calm aboard the Titanic, too, long after the collision, and an unreal attitude of nonchalance existed right up until the moment we were told we should get into the lifeboats. (“Only a precautionary measure, ladies.”)

Only then, as we collected around the boats, was there jostling and pushing, even though none of us knew at the time that those boats could take only 1178 people and we were 2207 passengers and crew.

“Stand back, stand back. Be British!” an officer barked, but the deck was sloping forward; water was pouring into the Titanic’s bow. I was just about to clamber into a lifeboat when a man stepped forward holding a bundle.

“Who will take this baby?” he cried.

Impulsively I reached for it, and with the child screaming in my arms, I found a seat for us. Even as we rowed away from the Titanic’s side, with distress rockets booming and blazing above us, we did not think the ship would sink, for we still believed that she was unsinkable.

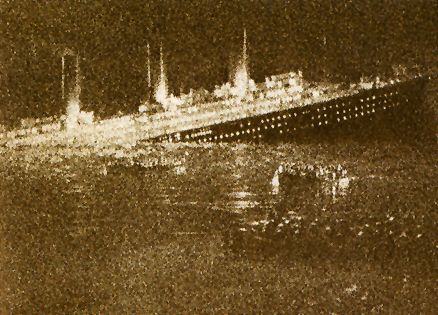

In all, it took three hours for the Titanic to die. That last hour was a time of mounting terror as we watched what we could not believe—the ship’s stern rising out of the water, hundreds and hundreds of men and women still aboard, an orchestra playing ragtime tunes, lights twinkling.

When at last the Titanic stood straight up in the water, tall and slender as a skyscraper, the master of arms in charge of our lifeboat—his name was Bailey—suddenly stood up.

“Scream!” he shouted at us. “Scream!” as though our noise would mask and nullify what was about to happen. There was no help we could give to those still aboard the huge sinking ship; screaming, at least, was something we could do.

And so it was that as the Titanic slid roaring and rumbling into the water, we were all yelling. In the midst of death we were filling our lungs with screams of life, like babies out of the womb.

Then the stillness. That unforgettable silence. The oars of our boat trailed lifeless as our rowers slumped forward. All of us sank within ourselves, unable to speak, think or feel. The baby whimpered in my arms. A low moaning rose from the women mourning husbands and children. We were exhausted, afraid, forsaken.

Once again Master of Arms Bailey got to his feet. His eyes flashed in the starlight and his walrus mustache quivered as he said in the stillness, “Please. I want you to sing with me. Sing now, all of you. Please.” And his deep, resonant voice rolled out with, “Pull for the shore, sailors, pull for the shore…”

The men at the oars straightened. Here and there a faint voice picked up the words. Cracked and quavering at first, the voices seemed to draw strength from the old church hymn that so many of us had learned growing up in England.

“Pull for the shore, sailors, pull for the shore!

Heed not the rolling waves, but bend to the oar,

Safe in the lifeboat, sailor, cling to self no morel

Leave the poor old stranded wreck, and pull for the shore.”

With that hymn, we were God’s people again, each bending to his or her task, trying to make others comfortable, soothing the children, consoling the bereaved, doing what had to be done throughout the remainder of the night.

When morning came, so too did the rescue ship Carpathia, and soon we were safe on her decks, the baby I had held in my arms safe in its mother’s arms again.

I was 27 years old the year the Titanic sank, an unmarried young woman on her way to live in America. The memory of that disaster has never left me for as much as a day, but it has not been as ugly to recall as some might think, for one can always bring something good out of every bad experience.

I learned that night to concentrate on living life. During those hours when death and life were suddenly so starkly delineated, I realized once and for all that there is no real certainty in man’s world. Unsinkable ships do sink.

Yet I believed then, as I believe now, that there is certainty in God’s universe. When we sang that old, very familiar hymn I was reminded that we in that lifeboat were among the living, and when one is alive there is work to be done—oars to be pulled, shores to be reached.

So it was that the Titanic taught me that I should never waste my time pondering the riddle of death—and I never do, for I am much too busy accepting life.

Download your FREE ebook, True Inspirational Stories: 9 Real Life Stories of Hope & Faith