One of the most frightening signs that there was something seriously wrong with me were the voices I began hearing in 1974.

At first they were just stray, nagging worries that dogged me through the day, self-doubts that we all have from time to time. They seemed to rise up out of nowhere—vague thoughts with an accusing edge: You really don’t work very hard, do you? Or I’d be alone in my car and it was as if I overheard someone whisper, Everyone knows Lionel Aldridge doesn’t care about his job.

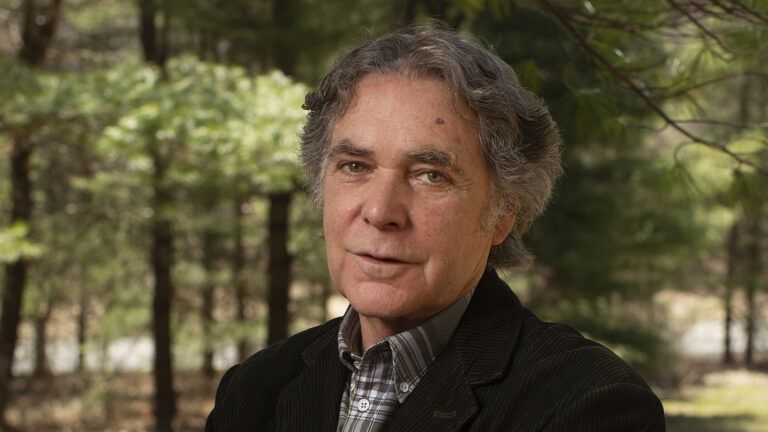

The fact was I worked hard and cared very much about my job. I was something of a fixture on the Milwaukee scene. After an all-pro career as a defensive end with coach Vince Lombardi’s two-time Super Bowl champion Green Bay Packers football team, I’d moved easily into the role of NFL commentator and local TV sports anchor. I had a successful, high-profile life.

That was before the voices.

The voices were very scary and confusing. I didn’t know what to do. I didn’t want anyone to find out the terrible things happening inside my head. As an athlete I’d been trained to be tough; it was not my nature to seek help. I wanted to be strong.

At first I tried to ignore them. I was just going through a bad period, I thought. But the voices grew more belittling and threatening, more real. I’d be standing in front of the mirror shaving when I’d hear from the next room, You don’t take very good care of your family. “That’s bull!” I’d shout. I’d search the house for my tormentor. “How’d he get in here?” I’d mutter, as my wife, Viki, shook her head in dismay. There never was any intruder.

If a co-worker at the station didn’t smile at me in the morning, a voice would hiss, See? He doesn’t think much of you either. He knows you don’t deserve your job. I became hard to get along with. I started talking back to the voices, bickering and pleading and cursing. I am a large and imposing man; it must have scared folks half out of their wits to see me shouting at people who weren’t there.

Rumors flew around town that I was on drugs. That was completely false, but I was in no shape to prove otherwise. I was getting worse. People wanted to help but they didn’t know how. “He’s under a lot of pressure,” I heard them say.

One night, attending a Bucks basketball game with a friend, I froze with terror as we moved in front of the crowd toward our courtside VIP seats.

“What’s wrong?” my friend asked.

“These people,” I stammered, “they…they know everything I’m thinking. They’re all watching me.”

I was dizzy with panic. I wanted to run.

“Take it easy,” my puzzled friend whispered, looking at me as if he suspected I was playing a gag on him. Then he saw the perspiration drenching my shirt collar. “Maybe you’re working too hard,” he muttered, putting an arm on my shoulder and easing me into my seat.

Soon that feeling of being watched wouldn’t let up, even on the air. Looking into the camera, I could barely hold my composure as I reported the nightly sports scores. The wide camera lens zooming in on me was a glistening, all-seeing eye that could plumb the farthest, most hidden reaches of my soul. Everyone who was watching on their TV sets, I was convinced, could see right inside my brain, where laid bare for all to look on in disgust were the grimmest secrets of my life.

I was sure there was a far-flung conspiracy to destroy me. I fought with total strangers on the street. I separated from Viki and our two daughters, and eventually divorced. I lost my job and my friends. There was nothing left but the voices shouting in my head, as real to me as an opposing 260-pound pulling guard on a goal line stand back in my playing days. My life spun out of control.

One night the voices commanded me to start driving. I didn’t want to leave Milwaukee. It had been my home for so many good years, and a part of me still understood that I needed a home now more than ever. But my state of extreme delusion robbed me of choice.

I hastily packed up the car with some old clothes and a few basics. Almost as an afterthought I threw in a Bible I’d owned since the Packers. I used to take it with me when I traveled with the team. Even now I’d read it to try and drown out the voices. What little relief I could get sometimes came from immersing myself in that old Bible.

I started to drive with no map or plan—I just filled up on gas and went. I tried to turn back; I couldn’t do it.

I crisscrossed the country in a wilderness of interstates. At first I slept in hotels, then motels, then flophouses. I went to Chicago, Kansas City, Dallas, Sacramento, Las Vegas. My funds evaporated and my credit cards were cancelled, so I started living in the car, occasionally washing dishes for food and gas. In Florida I ditched the car for a hundred dollars and hit the streets with just a battered satchel on my shoulder.

Occasionally I hung around a town for a while doing odd jobs, living on the streets and eating at soup kitchens. Quite naturally, people would stare at me, and that would only make my delusions of persecution worse. I never held a job for long. What could you do about a menial laborer who marched and sang for no reason and jabbered at people who were 2,000 miles away? Had I seen such a man on the street in Milwaukee only a few years before, I would have shaken my head sadly and crossed to the other side.

I’d become one of those lost, devastated souls. There were a lot of them out there with me, crippled by mental illness, but as I wandered the country I was only aware of my own haunted, unhappy world a million miles from the life I once had.

One night I slept in a field off an interstate near the Great Salt Lake. I didn’t notice when I woke up, but while I was sleeping my jewel-encrusted Super Bowl ring must have slipped off. Those rings are not easy to come by, and I’d hung on to mine as a kind of symbol of who I’d once been. No one ever questioned me about it. I guess they thought it was just some crazy piece of jewelry that a crazy man wore.

I didn’t think about the Packers much anymore, and when I discovered the ring missing, it was as if I’d been stripped of one final link with my past. I sat in the middle of a sidewalk and wept into my hands.

It wasn’t long afterward that I was gripped by a gruesome hallucination. I was hanging on a cross, like Jesus. Standing in a roadside ditch under a hot white cloudless Utah sky, legs together and arms outstretched, I vividly experienced my own crucifixion. It is hard to explain now, but in my tortured imagination I actually believed that I was living out the event. It seemed so absolutely real.

I remained that way for hours. People shouted from cars whizzing by on the desert highway. A few threw objects at me. But I was anchored to that spot, fully convinced that I could be seen hanging on a cross and no one cared.

“Help me!” I cried out, the sweat and tears streaking my dust-caked face. “Help! I’ll accept help from anyone.”

That night, exhausted and hungry, I huddled beside a bridge and read my battered Bible, the only thing left now from my old life. I still had moments when I could dimly perceive reality. A core part of me knew that I must get well. But that clarity was fleeting, and my madness always took me back in circles and filled me with hurt and fear.

I was reading Paul when I came across a passage that stopped me: “Earnestly seek the higher gifts.” I’d been taught that these gifts were spiritual, given by God to lift us up. Were they still there for me? I wondered what gift could be found in the demented chorus that chased me across the country. Those voices were so angry and critical.

Yet didn’t I know all along that there was one voice with me my whole life, a flowing, wordless voice that said, You are loved? It was the voice of God, a voice for all of us to hear in our own way. I’d never stopped believing in God, but His voice had been drowned out by my illness. When I stopped long enough to listen, I knew that with God I had hope, I had love. That was what Paul was talking about.

Eventually I wandered back to Milwaukee. The voices still besieged me. I lived on the streets. Being back brought me in contact with old friends. I was ashamed for them to see what I’d come to. I tried to hide. Yet for some reason I’d come back here. I knew that.

Finally, through the repeated intervention of people I’d known for a long time, I was committed to a hospital. I didn’t want to go in—I thought it was all part of the big conspiracy. Commitment is difficult legally, and I made it harder. Yet it marked the start of the road back.

I learned that I had paranoid schizophrenia, a physical disease that affects the mind. Hearing voices was one of the symptoms. Slowly the doctors hit upon some drugs that helped. Little by little my condition improved, the voices gradually subsided.

At first it was horrifying. It was an awful thing to face, like seeing a crazy man on the street and suddenly realizing that you are looking into a mirror. One day during therapy, I begged the doctor to show me one person who’d recovered from paranoid schizophrenia.

“Well, Lionel,” he replied, “statistically many people do recover partially, even fully.” He went to quote all the facts and figures.

“No,” I interrupted, “I want to actually meet someone who’s beat it.”

There was no one to show me. People who recover from mental illness rarely divulge that devastating stigma. It would have helped me to see someone who’d come back. “If I get out of here, Doc,” I promised him, “I’m going to make a point of talking about it.”

I did recover. Not without setbacks and relapses, not without moments when I thought I could never again face life, but I did get well with the help of friends, doctors who found the right medication to help me and the voice of a loving God.

I discovered new strategies to cope with the world. For a while, symptoms sometimes came back. Like one night after I got out of the hospital. I was walking up to a cafe near my apartment for dinner when suddenly I knew that every patron inside was saying terrible things about me. I stood at the door, terrified, my heart pounding. I was about to run home and lock myself in when I thought, No, you’ve got to do this. You’ve got to go inside and face these people.

Still I was convinced they were all talking about me. Well, I figured, maybe they’re saying good things like, “Hey, there’s Lionel Aldridge. He used to play for the Packers and then he got sick. Look how good he’s doing now.” If people really were saying bad things about me, I would have to forgive them. Forgiveness made what they said harmless; it didn’t matter whether it was real or imagined.

I went inside, sat down and ordered my dinner. The room was alive with chatter. I was almost too nervous to eat. Then slowly it dawned that these people were talking about everything in the world except me.

It worked. From then on when I thought strangers were talking about me, I always convinced myself that they were saying good things, or forgave them for the bad things I imagined them saying. And through the whole process I never stopped asking God’s help or listening for his voice.

In time the voices went away. I still see a doctor and take my medication, like anyone with a serious illness, but I am well again, well enough to keep a promise. Today I travel the country speaking to groups about mental illness and recovery. It’s vital for patients, families and even doctors to see someone who’s actually made it back.

In January 1985, the anniversary of the Packers’ first Super Bowl win 18 years before, I got a card in the mail from a bunch of my old teammates. They’d gotten together and commissioned an exact copy of the missing victory ring to give to me.

I knew that day that I had returned. Even when you think you’ve lost everything in your life, there is always hope of finding a way back, sometimes to an even better place.

I found my way, with the loving voice of God to guide me.