My son, Ryan White, died in 1990. Ryan, a hemophiliac, contracted a fatal illness from a type of blood product critical to people with hemophilia. But at the time no one realized that a new and deadly virus was then lurking in the nation’s blood supply.

Ryan had just turned 13 when he was diagnosed in December 1984. I was a single mother. We lived in Kokomo, Indiana. Ryan had been born there, as had his younger sister, Andrea. So had I, and my ex-husband and my parents. My mom’s big worry when I was growing up was that I might marry someone who would take me away from Kokomo. You weren’t ever supposed to leave Kokomo. Kokomo took care of you. It was home. Then Ryan was diagnosed with AIDS.

When Ryan first became sick, we took him to the James Whitcomb Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis, where they discovered that Ryan had a rare form of pneumonia that usually indicates AIDS. But it was a few days before his physician, Dr. Martin Kleiman, knew for sure. I didn’t want to tell Ryan until after Christmas. Ryan loved Christmas, and Dr. Kleiman couldn’t guarantee that this wouldn’t be Ryan’s last.

“The disease is so new, and so few children have it, that we just don’t know how long Ryan can hang on,” he explained.

Looking back, two incidents at Riley should have warned me of what was to come. First was a snatch of conversation in the cafeteria, a nurse speaking to a doctor: “I will not go into that boy’s room,” she insisted, trying to keep her voice low. “I don’t care what they say about not being able to catch it; I’m not taking a chance.” It wasn’t just what she was saying. It was the hard edge of fear in her voice.

Then two of Ryan’s favorite teachers from his middle school showed up to deliver a big batch of get-well wishes from his classmates. Though Ryan didn’t know about his diagnosis yet, I thought it was time to tell his teachers. They paled and, fumbling, pushed the cards into my hands. “We shouldn’t bother him,” one of them said. Quick as that, they were gone. Strange, I mused, they drove an hour to see Ryan, all the way from Kokomo.

By Christmas Eve, Dr. Kleiman was able to take Ryan off the ventilator and removed his chest tube so he could talk again and celebrate Christmas. The day after, I told Ryan he had AIDS.

He didn’t cry. He didn’t even seem scared. He just wanted to know when he could go back to school. “Mom, I want to get on with my life,” he said.

Before I left his room that night I switched on a little plastic guardian angel that church friends from Kokomo had given us when Ryan was in and out of the hospital with hemophilia. It was just a battery-operated night-light, but Ryan always had it by his bed whenever he was hospitalized.

In the morning Ryan told me something incredible. “Mom,” he said, matter-of-factly, “I saw Jesus last night.”

I didn’t know what to say.

“He told me that I had nothing to worry about,” Ryan continued. “He promised he would take care of me.”

“Ryan, what did Jesus look like?”

Ryan kind of smiled. “Well, he didn’t look anything like that picture I have hanging in my room.”

He never again mentioned the incident. But I thought of it often. I hoped it meant that God would work a miracle and cure Ryan. Is that what you mean, Lord, by taking care of him? Are you going to give us a miracle?

Ryan came home in February but missed the rest of the school year. By summer he was well enough to get a paper route and hang out with his friends. He began agitating to go back to school. Ryan could never play sports because of hemophilia, so he poured all his energy into his studies. He was desperate to go back. He was bored to death sitting around the house watching I Love Lucy reruns.

“All right,” I said. “I’ll tell them you’re coming back in September.”

It wasn’t going to be that easy.

The school board wouldn’t let him back. Everybody was afraid. The board claimed it couldn’t guarantee the health of Ryan’s fellow students, despite overwhelming medical evidence that AIDS wasn’t contracted through casual everyday contact. Finally a court forced the board to relent and Ryan returned to school.

But only for a day. A group of parents promptly brought suit to bar Ryan and he was sent home until arguments could be heard in court. Months dragged by. Eventually a judge affirmed Ryan’s right to attend school. But by then, after more than a year of bitter legal combat in the center ring of a national media circus, the damage was done. Kokomo had hardened its heart against one of its own.

Still, Ryan was glad to be back; he even agreed to endure some completely unnecessary “precautions.” He drank from a separate water fountain and used a separate bathroom. He ate with other students but was forced to use paper plates and disposable utensils. He wasn’t allowed to take gym or use the locker room or pool.

Crazy rumors spread: that Ryan spat on food and tried to bite people. Parents didn’t let their children associate with him. When he walked down the hall at school, kids ran away screaming. One day Ryan found his locker defaced with obscenities.

“Mom, are these people nuts?” he demanded. “I don’t even know what half those words mean!” I knew how he felt. At my job with one of the huge auto plants in town, I was getting threatening anonymous notes attached to my time card.

Usually Ryan was able to shrug these things off. He was tough. He’d wanted to fight this fight. He’d always been more disgusted with the people who secretly supported him but were afraid to stand up than with those who openly attacked him. Now he worried about Andrea, his grandparents and me.

On Easter Sunday 1987 we were sitting in the back pew of our church—Ryan, Andrea, my parents and me—so Ryan’s cough wouldn’t upset people. When it came time for the traditional Easter greeting of peace, folks turned to the people in the pews behind them with a handshake and the words “Peace be with you.” As the greeting rolled to the back of the church, I glanced over at Ryan. There he stood, gaunt, his growth stunted by AIDS at five feet, with his hand outstretched. But no one would shake his hand.

Afterward, as we walked to my father’s car, I cried out silently, Lord, I thought you promised Ryan you would take care of him. Every night Ryan and I had thanked God for another day. Now I wondered how much more my son could take. Ryan had been in and out of the hospital with the kind of illnesses that plague AIDS patients. He was on a medical roller coaster, and it was taking its cruel toll. Yet he held on. He had faith. Each time he was hospitalized, he brought his little plastic angel. But I was still waiting for a miracle.

The next Sunday, while we were at church, a bullet shattered our home’s picture window. “Mom,” Ryan announced, “it’s time to get out of Kokomo.”

I dumped our house at a tremendous loss—everyone dubbed it the “AIDS house”—and we moved 20 miles south to a community called Cicero.

To our amazement, Ryan’s new high school accepted him with open arms. The students themselves had decided to get together for AIDS awareness classes. They invited expert speakers and offered counseling to anyone who was afraid. The truth was, when the issue was left to the kids, they handled it much better than the adults.

Ryan’s life had taken so many incredible turns. By now the whole country knew of his plight. He’d been on Nightline and the Today show and had made hundreds of new friends. He traveled the country speaking to people about AIDS. Everywhere, AIDS patients told Ryan the same thing—because of his public battle, Ryan had eased the way for them. “See, Mom,” he said, “some good did come from that mess back in Kokomo.”

I thought a lot about Kokomo. You don’t just walk away from your hometown. I had family there. The local paper stood behind us, and our true friends never faltered. Ryan put it in perspective. “Look,” he explained, “people were just doing what you were trying to do—watching out for their kids. They were scared to death, and that’s why they acted so crazy. In a way, I really can’t blame them—though they were wrong.”

Ryan didn’t have time to be bitter. He had forgiven. I prayed to find that same forgiveness.

In the spring of 1990 Ryan began slipping, and while we were in Los Angeles for an AIDS benefit, he became very ill. As soon as we got back to Indiana, Dr. Kleiman admitted him to Riley. Ryan knew it was bad. “I’m scared this time, Mom,” he said.

He was 18.

Over the next week Dr. Kleiman exhausted the medical options. Ryan’s immune system was failing, and he slipped into unconsciousness. “Jeanne,” Dr. Kleiman said, “I give him a 10 percent chance of making it. And the only reason I give him the 10 percent is because he’s Ryan.”

Ryan had always said that when it got to this point, it would be harder for me than for him. Now I was afraid he was struggling to hold on to life for my sake. “Just let go, sweetheart,” I whispered to him. “It’s all right now.”

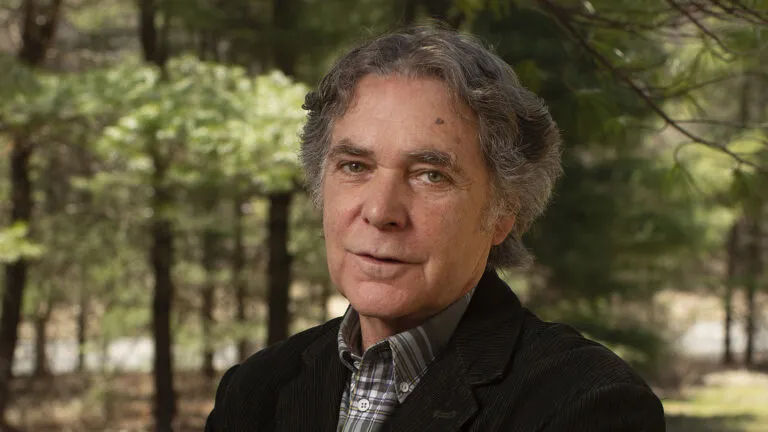

Ryan White, who died in 1990. Credit: The NAMES

Project Foundation

On Palm Sunday, 1990, Ryan let go. Like the day’s last rays of sunlight, his breathing faded and then his heart stopped. Dr. Kleiman nodded. I leaned over and gave my son a last kiss. Then I reached for his guardian angel night-light and switched it off.

A week later, after the funeral, I put the angel on our mantel next to Ryan’s high school picture. I stared at that angel, remembering how it had been given to us by our Kokomo friends so many years before. In Ryan’s last week, word came through that the churches in Kokomo were praying for him. That was the Kokomo I wanted to remember.

And then, suddenly, looking at Ryan’s angel, I knew that God had worked a miracle. He had taken care of Ryan. How else could Ryan have survived for nearly six years when the doctors had given him only six months? God chose Ryan, an average boy from an average town in Middle America, to do his work—to be an example in the face of ignorance and prejudice and fear, and to sow compassion in the heart of the nation.

Four years later, I still keep his angel on our mantel. Ryan has not been forgotten. The other day at the mall I noticed someone staring at me. A few seconds later she came over. “Of course,” she said, “you’re Ryan White’s mother.”

For the life of me, I can’t think of anything better to have been.

Update: Jeanne White-Ginder has remained an activist in the 30 years since her son, Ryan, died. Now 72 and living in Florida, she keeps up a busy schedule, speaking at AIDS fund-raisers and on behalf of the National Hemophilia Foundation. In 2007, the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis opened a permanent exhibit called “The Power of Children.” The exhibit includes a recreation of Ryan’s bedroom alongside replicas from the lives of Holocaust victim Anne Frank and civil rights pioneer Ruby Bridges. Ryan’s beloved guardian angel night-light plays a prominent role in the exhibit. It sits on Ryan’s bedside table and lights up during a multimedia presentation about Ryan and his fight for acceptance. Jeanne returns to Indiana four times a year to talk to children at the museum. “I’m so fortunate I got to tell my story in Guideposts,” she says. “Most of the media coverage about Ryan left out the spiritual side, but that’s what got us by. That was everything.”

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.