It’s World Series time, and I think I finally understand my late Uncle Vince, a World War II combat veteran. You’re asking what the two things have to do with each other, right?

Vince was my mother’s younger brother, the youngest of the six Rossiter kids. The Rossiters were a voluble, competitive, opinionated, smart family. Except for Vince. Smart, yes. He was an accomplished civil engineer who helped complete the Pennsylvania Turnpike, one of the country’s first.

But he was not those other things. He lived alone and was shy to the point of seeming withdrawn. He never married or seemed to have a close relationship (everyone else did their competitive best to add as much boom to the baby boom as possible).

He ate dinner almost every night out in Paoli, PA, at his oldest sister, my aunt Cass’s. He smoked like mad, the only Rossiter who did, and died relatively young of lung cancer in a family known for longevity. But it wasn’t really lung cancer that killed him.

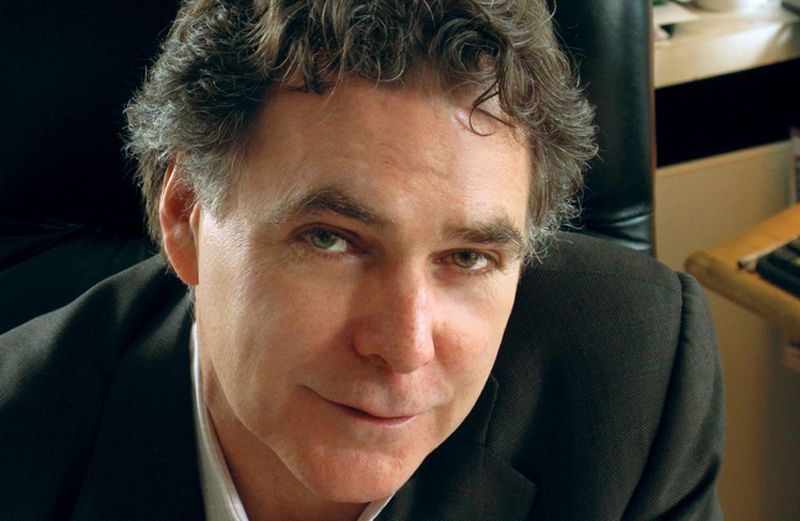

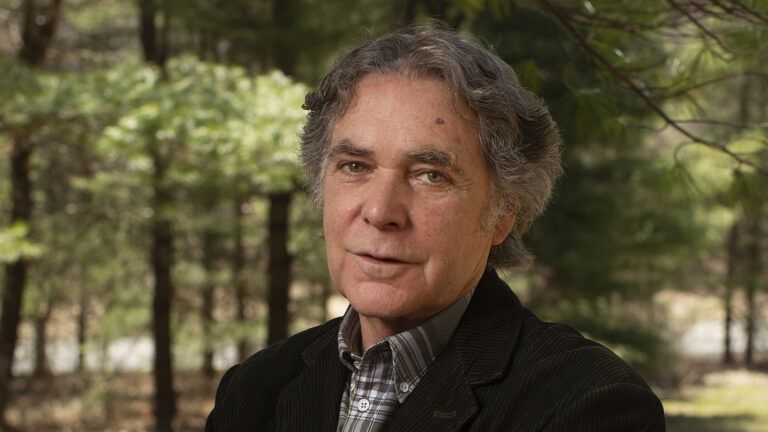

That realization has slowly dawned on me this year editing our series in Guideposts, “Our Returning Troops." It really hit home this week when I edited the last piece, slated for the December issue, written by another member of the Greatest Generation who served, longtime roving editor John Sherrill.

John tells of his horrific combat experiences in Italy. “But we generally didn’t talk about it,” John said. The Greatest Generation simply tried to soldier on after the war was over. “We just buried those terrors and that pain.”

Except sometimes when you bury that kind of pain it only grows roots deep into our psyches. John still had nightmares about the war decades later–he urges today’s vets to share their war experiences so that we can all help them bear their burdens.

Did Vince have nightmares? They used to talk about how he was blown out of a tank during the Battle of the Bulge. His brothers Paul and Jack said it half-jokingly, half-sympathetically, and my mother seemed to know somehow that Vince did not come home from the war the same little brother.

His life had been conscribed–his isolation from all except family, his rigid routine. He had two weeks of vacation. He always took a week in August to go down to the Jersey Shore, where we all were. He’d sit in a beach chair and smoke.

Then in October, since he had a fanatical love for baseball, he took the week of the World Series off so he could watch the games, which were played in the daytime, out in Paoli on Cass’s black and white Philco.

I’m not sure PTSD was even a clinical term back then. I’m sure Vince (or any of that Rossiter generation) never went anywhere near a therapist. A priest, maybe, about the guilt he might have felt surviving a military campaign that so many didn’t. Vince was sensitive.

It might have tormented him that he lived while others died. He never missed church, and I am sure that comforted him, and he listened to every single Philadelphia Phillies game.

The Phillies were the only thing he would let himself get emotional about, at least openly. Baseball comforted him too, took him away temporarily from the lingering dread he brought home from Europe.

But not enough. I think it was really PTSD that did him in, holistically. He was only in his 60s when he died. I wish I had a picture of him. I probably do somewhere if I wanted to dig it up.

But all I have to do is close my eyes and see him sitting in an armchair on his vacation watching the World Series and taking long drags on a cigarette, trying to lose himself in something bigger than his suffering.