The airline seat was cramped. I stretched and shifted my big frame restlessly—no, let’s be honest, nervously.

I looked across my row out one of the small, oval-shaped windows. Green to the horizon, a blurry expanse of trees and grassland. That’s where we were going, four friends and I, to Uganda, Africa, on this, my very first mission trip ever.

Actually, this was my first international flight, first time using a passport. That wasn’t the only reason I was nervous. My buddies, Jeff, John, Chris, Dan, and I were prepared. We had raised enough money, arranged for places to stay and plotted our route. We planned to spend half of our time in Kampala, the Ugandan capital, where we would visit an orphanage sponsored by my church and meet a girl, Betty, my wife, Shauna, and I sponsored.

The rest of the trip we’d spend in Jinja, a smaller city about 50 miles away, where a pastor my wife and I had long supported ran a school. We had prayed. We had each other’s backs.

And yet, watching the Ugandan landscape near as the plane descended, I was gripped by a single terrifying thought: What on earth am I doing here?

I couldn’t afford this trip. Not the money, not the time. When I gave in to the guys’ prodding—“But Brett, the church travel agent says we could wait ages before flights get this cheap again!”—I had been out of work for more than a year. I’d lost the restaurant regional-manager job I’d been counting on to put my son and daughter through college and to keep Shauna and me in the nice house, nice cars and nice clothes we’d gotten used to. I’d tried another management job with a fast-food franchise. But I’d left after a few months. It just didn’t feel like the right fit for me.

Nothing felt right, and I couldn’t figure out why. Ever since I was in fifth grade and my dad walked out on our family, I’d vowed never to rely on anyone but myself. I’d worked hard and reaped the rewards. I was a good provider. So what if I hated the work? The restaurant business paid well, and that’s what was important to me. But what a dismal grind it had become. Whatever passion I’d once had was long gone.

I yearned for something deeper, more fulfilling. Don’t be a fool, I reprimanded myself. While I dithered, bills piled up. What was I supposed to say to Delanie, our eight-year-old, and Weston, our six-year-old? Sorry, kids, Dad’s having a midlife crisis, so no toys this year.

Already we’d moved to a smaller house, downgraded to a used car, cut out restaurant meals—how weird, me, the restaurant guy, not eating out!—eliminated shopping sprees. Still, the bank balance plummeted. I felt paralyzed. Afraid. Lost.

So what was I doing on this airplane? It was partly Shauna’s fault. Through all the months of my job searching, she hounded me, of all things, about going to Africa. She wanted to visit the God Cares schools, which our church sponsors in Kampala, and see Pastor Fred Tumwebaze in Jinja.

We had fond memories of Fred. He’d come to the U.S. several years before to raise money for his school, and my family had put him up for a while. What a lovely, faith-filled man, so determined and resourceful.

My argument to Shauna was, “We already give Pastor Fred money. Why waste thousands more going to see him?” Then I got the fast-food job and, figuring we could afford it, told Shauna she could go if she was so set on it. She bought a ticket—and ended up leaving just days after I quit. That trip blew a huge hole in our already tattered budget.

And yet, when I picked her up at the airport two weeks later, the change was unbelievable. Shauna was radiant, as if she’d come back from a luxury vacation. Except she’d been giving out shoes and helping feed kids, many orphaned by AIDS, in makeshift schoolrooms.

“The kids, Brett,” she kept saying. “It would break your heart. Except it doesn’t, because their hearts aren’t broken. They live their faith like I’ve never seen.” She fixed me with a look. “You have to go. I don’t care about the money. You just have to go, Brett.”

Don’t care about the money. Right then, with Kampala’s sprawling outskirts racing past the airplane window, I was caring about the money—a lot. How could I have been so foolish? That’s it, I thought. When I get home I’m totally buckling down and finding a real job. No more wasting time.

The plane landed and a few minutes later the five of us were descending stairs to the tarmac. Warm, tropical rain fell, darkening the sky over low hills in the distance. I took a deep breath. No turning back now. Pastor Dongo, the head of God Cares, met us. As we drove through Kampala’s pell-mell streets to the school, all around was an almost incomprehensible mix of gleaming towers, shanties, red dirt roads, green hills and, of course, people—people walking, careening on motorbikes, crammed in minibuses, dressed in suits, wearing rags.

My head spun. We checked into our hotel and found it had no electricity. Then we drove to the school.

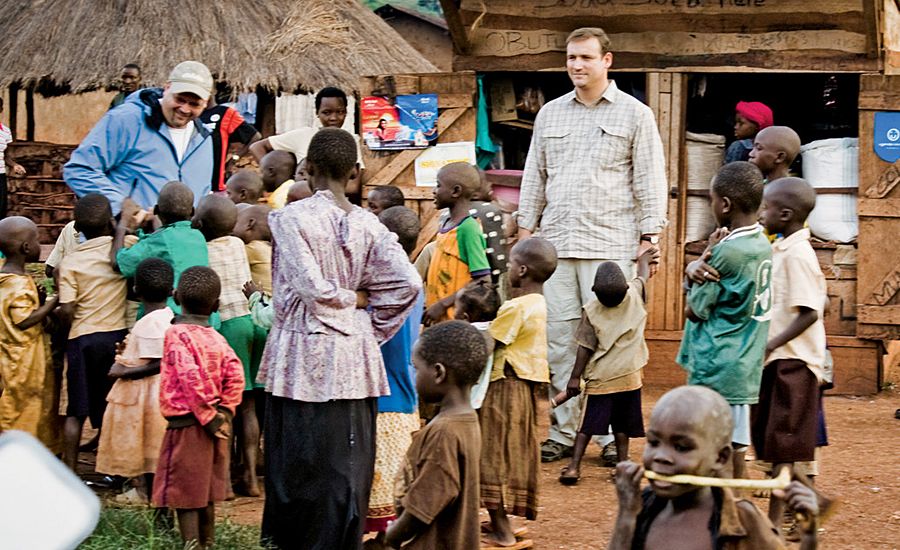

Before we even climbed out of the minivan the kids surrounded us. Hundreds of kids, all wearing school uniforms, blue-collared shirts and shorts. They tugged at us, laughed, danced. It was like we were celebrities. I

reeled from the realization—these kids had so little, my arrival was a big deal in their world. Pastor Dongo showed us around the five-story building that housed his school, a kitchen and dorms for those children who had no family. The building had been paid for by an American donor. Like our hotel, it had no electricity. The staff cooked over a wood fire in a few—too few, they told us—giant pots.

“We need to buy them a pot,” Jeff said. I nodded, dazed, trying to take it all in. I had spent my life in an industry dedicated to selling people oversized helpings of food. Now, here, food was a scarce necessity.

A few minutes later Pastor Dongo introduced me to a teenage girl with short hair and a bright smile. “This is Betty,” he told me. Shauna and I had been sponsoring Betty for about a year, thirty dollars a month for meals, schooling and her uniform. I handed her a gift my kids had helped me put together: a backpack with notebooks, pens, paper and the equivalent of twenty-five dollars in Ugandan currency.

Her eyes widened. She thanked me over and over, holding my hand. I tightened my jaw, determined not to cry. I didn’t want to embarrass her. All I could think was, I spend more than twenty-five bucks a month on coffee at Starbucks.

The hours and days that followed were a joyful, exhausting blur. We bought the big pot, gave out toys, candy and school supplies, and talked to the kids about the Bible and faith. Pastor Fred picked us up midway through and drove us to Jinja, where we realized that in Kampala we had been living in comparative luxury.

The Omega School was a complex of plywood and cement buildings with—a great luxury in that area—flush toilets. We bought 250 pairs of shoes and socks and gave them out, bought bicycles for the pastors and played with countless children.

A teacher named Ricky Kahudu mentioned a side project he ran in Kampala, a group of about 70 churchwomen, most of them widows, who made baskets and beads out of varnished recycled paper to sell to tourists. “Not much of a market,” he said sadly.

To be polite, I took a look at some beads he had brought with him from Kampala. Whoa, I thought. These are beautiful! Delicate shell shapes of yellow, turquoise and other bright colors were strung on simple strings. The last thing they looked like was recycled paper. “I have some friends back home who’d like these,” I said to Ricky. “Can I take some?”

He nodded eagerly. I stuffed the necklaces in my suitcase and we said our goodbyes.

I was conflicted about leaving. But I knew for sure why I’d come to Africa. I knew why Shauna had looked so radiant after her own trip. It wasn’t just the kids’ and their teachers’ resilience in the face of crushing poverty. It was their complete trust that God would provide and their equal determination to use his gifts to the full.

A few days after I got back to Texas, some friends from church came over to our house to hear about the trip. One of them saw the beads I’d brought from Ricky. “Wow, these are beautiful,” she exclaimed, fingering a multicolored necklace. “Can I buy some?”

“Sure,” I said. She must have told friends, because soon our phone was ringing with requests for beads. We ran out fast and, after sending Ricky the money we’d made, I asked if he could send some more. He did, and we sold those too. We sent the Ugandan widows the money.

Soon, with surprising speed, we were running a business, ordering beads and baskets from Ricky and selling them to jewelry and craft stores in Fort Worth. Everybody benefited—Ricky and the widows got paid for their work and Shauna and I made enough to support ourselves. We even created a website.

It wasn’t until a while later that I realized the beads weren’t just some side project while I looked for a real job. In fact, I hadn’t sent out a résumé in a long time. The beads and baskets were the job. Sure, it pays nothing like the restaurant business. But my family always has enough.

More than enough. All those years I had been searching for a job with meaning, work that felt spiritually fulfilling. What I didn’t understand was that you don’t find work like that just by sending out résumés. You find it by trusting, living your faith like the kids and pastors I met in Uganda. Once I did that, the real Provider showed up big time. He gave me everything I needed.