Every day, the humiliation began anew. At the Jewish high school I went to in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, we didn’t have a gym teacher. For PE, we all lined up, as if facing a firing squad. The two most athletic boys picked teams for basketball.

The best players were chosen first, a rigid caste system that seemed passed down by Moses. I looked on, hoping God would make another miracle happen and let me not be the last boy chosen.

Community Newsletter

Get More Inspiration Delivered to Your Inbox

“Not him,” I heard the other boys whisper. “Not Joe.” It shattered my self-confidence. Through four years of high school, I never touched the ball.

I didn’t blame the guys. I was a total klutz. The ultimate benchwarmer. Hopeless at any kind of manual dexterity. I was a whiz at math, but figuring out the area under a parabola wasn’t going to win me any friends. Not like basketball could. I loved the speed, the back-and-forth, the smoothness of a jump shot and the drives to the basket. But my Brooklyn, New York, neighborhood of Orthodox Jews had no courts to even practice on. I was never going to be one of the jocks. During senior year, I took a job aptitude test. The results: accountant or engineer. If only I could be a gym teacher… If I were in charge, I’d make sure that kids like me weren’t excluded. But to be a coach, first you had to be an athlete. As if that would ever happen…

So I became an engineer. I got hired by Hughes Aircraft in California. I designed circuits for NASA’s Surveyor program, which in 1966 began sending unmanned spacecraft to the moon, setting the stage for Neil Armstrong’s giant leap for mankind. For the first time in my life, I was in demand. I got hired by another major defense contractor and helped create a system for sending messages across a computer network, a big deal at the time. But that’s not how I saw myself. I was still awkward, physically and socially. I worked 60 hours a week and didn’t do much else.

Then one day I went for a run. In California, in the 1980s, that’s what everyone was doing. I made it only a few blocks. Still, I hadn’t tripped over my own feet. I felt alive, rejuvenated. I started running more, a mile or two every day, my legs slowly getting stronger, more agile.

When I told my neighbor Mark, he said, “Come play basketball with us. We have a pickup game every Sunday.”

“You mean, I’d actually play?” I said.

Mark looked puzzled. “Of course,” he said. “What else would you be doing?”

This time I didn’t have to wait to get picked for a team. “Joe’s with us,” Mark said. There was only one problem. I had no idea how to actually play. I spent the entire game running madly around the court. I never touched the ball. I didn’t care, and no one else seemed bothered either. I was in seventh heaven.

For some 10 years, I played every Sunday—until Mark injured his knee and dropped out. My skills never really improved, but my self-confidence grew. I made friends. I tried other sports: tennis and skiing. I even joined an Israeli dancing group. If that wasn’t a miracle, I don’t know what was.

Work was a grind. I’d never wanted to become an engineer. I fantasized about chucking it all and pursuing my dream of working with kids. I’d seen what sports had done for me. If I could take up a sport, anyone could. They just needed the right encouragement, the chance to play against players of similar ability—the thing I’d never gotten in my pickup games. But I had no experience coaching. Was it too late to chase my dream?

In 2005, I retired at 62. I took a class at Santa Monica College called Beginner’s Basketball, designed to teach the basics of the game. I learned how to shoot, diagram a play, grab a rebound. Then, for two years, I took courses at California State University, classes on kinesiology—the science of human movement—how to teach athletics, how to run a class. I worked with kids in schools as part of my studies.

I volunteered to help with gym classes at an elementary school. It had eight full-size outdoor basketball courts. Every day at recess, I watched the star athletes take charge. Kids who had been playing on elite travel squads since second grade. The kids who were lousy watched silently from the sidelines.

“Couldn’t we dedicate one court for the kids who like sports but aren’t very good?” I asked the principal one day.

He scowled, staring at the sea of pintsize LeBrons. “Then there wouldn’t be enough courts for the ones who can actually shoot,” he said. “Dumbest idea I’ve ever heard.”

A Cal State instructor suggested I talk to someone heading up the basketball league at a local park. I found Randy Rosen. “Basketball for the athletically challenged?” Randy said when I told him my idea. He was clearly a jock. I waited to be shot down. “I like it,” he said instead. “How else are they going to learn? Let’s put it in the schedule. We’ll call it Benchwarmers.”

I got to the gym early that first night, giddy with excitement. One eight-year-old girl showed up. “You’re going to need more players, aren’t you?” her mother asked. I worked with the girl one-on-one for two weeks before pulling the plug. All those years I’d dreamed of being a coach, all the time I’d put into learning the game. Maybe it had been a dumb idea all along.

“Don’t give up,” Randy said. “We’ll try again next season. It’s going to take some time to get the word out.”

A year later, eight kids signed up for Benchwarmers Basketball. Just looking at them, I could tell they had way more enthusiasm than talent. One boy tripped walking out to center court. Perfect, I thought.

After a quick shootaround, I divided them into two teams. No big welcome speech. No vision statement. I wanted the focus to be on playing basketball.

I tossed up the ball for the tip-off, and the tallest boy slapped it to a teammate, who promptly dribbled it off his foot. The ball almost rolled out of bounds before another boy snagged it and hurled it toward the basket, missing the backboard by two feet. The kids were awful. It was beautiful. I’d never been so happy.

Each week for 10 weeks, they came back for another game. I didn’t give much instruction, but every week they got better. They learned by doing. The smiles on their faces were my reward. “This is fun,” one boy said. “I didn’t even know I could play basketball!”

The parents couldn’t stop thanking me. “This program saved my son’s life,” one mom told me. “He didn’t think he was good at anything. You’ve helped him believe in himself.”

I remembered how rejected I’d felt in school. How could anything good have come from that? And yet I would have never related to these kids otherwise. I had been chosen, from the beginning, for a position I was perfect for.

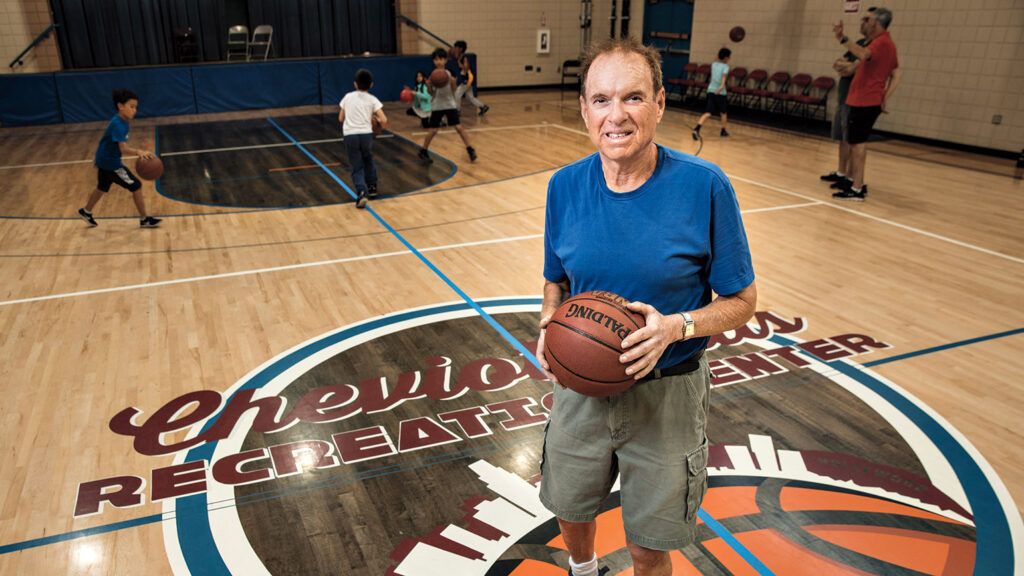

It’s been 11 years since I started Benchwarmers Basketball. Today more than 40 kids play, divided into two age divisions, over two 10-week seasons. It thrills me to see their self-confidence, as well as their athletic abilities, grow. The truth is that the Benchwarmers inspire me. Every week, I play in a pickup game I started for klutzy adults. I’ve gotten better too. And I’m taking piano lessons, a challenge for someone with no manual dexterity. I’m willing to take it slow. I’ve learned our greatest gifts aren’t necessarily the ones that come easily.

Interested in starting a Benchwarmers program in your community? Contact Joe Bock at joebock3@yahoo.com.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.