I have played in many memorable concerts over the years as a professional violinist.

None meant more to me than the one I was about to play at Tabernacle Presbyterian Church in Indianapolis.

The sanctuary hummed with voices that afternoon as concertgoers arrived and took their seats in the pews. To my amazement, the church was nearly full. Ushers had to run to the office to print more programs.

I’m always a little keyed up before performances. That day, I could barely contain my emotions.

I had organized this concert. I’d asked the musicians, sent out invitations and selected the music, a mix of well-known composers (Bach, Brahms) and lesser-known contemporary pieces.

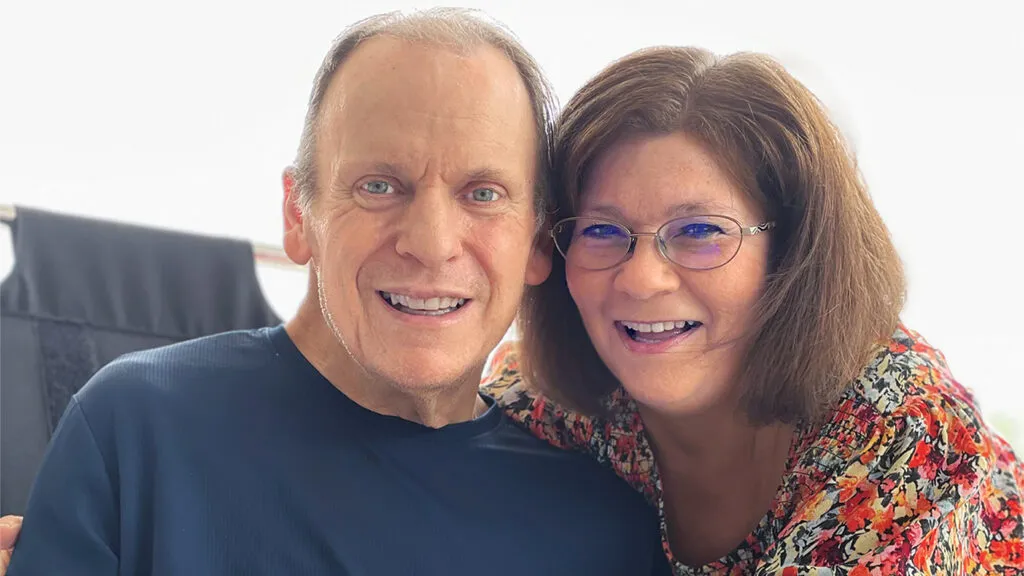

Most important, I had brought the guest of honor, sitting in the front row and looking no less dear to me than the day we married three decades earlier.

Mark and I were no longer married. It had been six years since we divorced, after everything in our once happy household was turned upside down by changes in Mark’s personality that we both struggled to understand.

Yet here was Mark at a concert organized by me, dedicated to him. His name was on the cover of the program, above a picture of one of the violins he had crafted as a luthier, a master string instrument maker. Every string instrument on stage that afternoon had been made by Mark. The musicians all knew and admired him.

How did all of this happen? It’s a love story—our love story. But there’s more. Through heartbreak and healing, Mark and I have learned about the deepest love of all: God’s.

Mark Womack and I were brought together by music.

I was 28 years old, a professional musician playing with an orchestra in Knoxville, Tennessee. It was 1985, and the orchestra’s season had just ended for the summer. I heard the Memphis Symphony had full-time violin openings.

I signed up to audition. A friend in Memphis offered to host me. The evening I arrived, Mark came by my friend’s house to drop off her viola, which he’d repaired. She invited him to stay for dinner.

Over pizza, I told Mark about a strange buzzing I’d heard in my violin. “Let’s take it to my workshop after dinner,” he said. “I’ll take a look.”

Mark quickly diagnosed the problem and made a few adjustments. I couldn’t help noticing how handsome he was, gentle and polite. He treated my violin with the same care he would have given to a world-class instrument.

At the audition the next day, I was surprised—and thrilled—when Mark showed up and invited me to lunch.

He came by my friend’s house the following evening and cooked dinner—he even washed the dishes! We went for a walk, and I didn’t try to conceal the fact that I was head over heels in love.

I won the audition and moved to Memphis. Mark and I married two years later. It seemed like a perfect match: a violinist and a violin maker. Though I’m Jewish and Mark is Christian, we agreed to respect each other’s beliefs and raise our children Jewish. (Children are considered Jewish if their mother is Jewish.)

Soon after marrying, we moved to Indiana, where Mark had been offered a job at a reputable violin shop. I found work teaching at the University of Indianapolis and joined the Indianapolis Chamber Orchestra. I formed a klezmer band to play the folk music of Eastern European Jews.

Mark thrived, earning a reputation as a skilled and meticulous craftsman. While I was pregnant with our daughter, Julie, he made a violin for me. He started his own business, working from a studio in our garage. After one of his violas was played at a prestigious convention, the business took off. Musicians from all over sought out his instruments. Mark won awards, including four silver medals from the Violin Society of America.

Mark was in his workshop by sunrise. Often he worked late into the night. Julie hung out in the workshop after school. Our house was filled with music—me practicing, the klezmer band rehearsing, Julie singing scales. She had her eye on a vocal career.

There was one shadow in our happy family. Mark suffered from clinical depression, but antidepressants kept symptoms at bay. Then, about 20 years after we married, the medication suddenly stopped working. Almost overnight, Mark’s personality changed.

He began going to bed early and sleeping in. Some days, he never made it to his workshop. He stopped playing racquetball and reading books, two favorite pastimes. He grew quiet, moved more slowly. Often he seemed confused. Defeated.

Julie and I fretted and tried to help, but Mark waved us away. He began to lash out. The slightest mistake would set him off. He’d yell at himself or whoever happened to be in range.

Work deadlines came and went. Once, a customer came to pick up an instrument and Mark was forced to admit he’d lost it. Months later, I found the violin wedged between two pieces of furniture.

Our family depended on Mark’s income to pay our bills. Yet every time I tried to bring up the subject, Mark would fly into a rage. I panicked about our finances. I prayed every day for God to heal Mark and look out for us.

I finally persuaded Mark to see our family doctor. The doctor immediately told him to seek psychiatric help, but Mark refused. His behavior toward me became so alarming that I feared for my safety.

I had no choice. Though I loved Mark no less than I did the day I married him, I could not remain in our house with him. We separated, and I filed for divorce.

Julie was at college. I moved into an apartment. I grieved the end of our marriage. “What do I do now, God?” I asked. I implored God for answers. How could two people so in love end up like this? Hadn’t he brought us together?

Mark moved in with his parents in southern Indiana. Partly for Julie’s sake, I kept in touch.

“What I did was wrong,” he said during one of our occasional calls. “I don’t know what’s happening to me. I’m sorry. For everything.”

“I forgive you,” I said. And I meant it. I still didn’t understand what had happened. But I found it impossible to hold on to negative feelings. There was only compassion. Mark seemed broken. I urged him to seek help.

“Maybe later,” he’d say.

He moved from job to job. Each time, he was let go after missing deadlines, getting lost or not following through with tasks.

Once, in Indianapolis to see Julie, Mark got confused while driving and had an accident. The repairs took a long time because he couldn’t remember insurance information. I let him stay with me.

He went out for coffee one day and didn’t come back. A police officer called me. “Do you know a Mark Womack?”

“Yes,” I said apprehensively.

“He tried to enter a stranger’s apartment,” the officer told me. “He got confused and thought it was your apartment. He gave us your number. We’ll bring him home.”

Another time, I asked Mark to help me cut a piece of wood for a bookcase. I watched as he tried and failed three times to cut a simple six-inch length of wood.

He was 51 years old. What was happening to him?

The answer finally came at Mark’s fourth and final job. He confessed to the shop owner that he had forgotten how to make a violin. In tears, he was taken to the hospital. Doctors diagnosed early-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Further evaluation led to a diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia, or FTD.

At last, everything made sense. FTD is characterized by dramatic changes in personality, typically starting in the patient’s forties. It is often mistaken for severe depression at first. Displays of anger and aggression are common. Mark’s rages weren’t really about me at all. He was frightened and ashamed of changes in his brain he didn’t understand.

I was stricken with guilt. If only we had known! I never would have divorced him.

Mark’s father had passed away by this point, and his mother was unable to take care of him. Julie and I were all Mark had left.

We didn’t know how to care for someone with dementia, but we vowed to try. I barely supported myself as a musician, and Julie was in New York studying to be a cantor—an ordained spiritual leader who chants liturgical prayers and performs other important clergy duties at a synagogue. Friends, colleagues and other family members cautioned us against taking on such a huge responsibility.

I did the only thing I knew to do. I prayed. Julie did too.

Immediately help turned up. People from my synagogue guided me to an elder law attorney. Julie and I filed for guardianship of Mark, which enabled us to access benefits to pay for his care. We found an assisted living facility and got him moved in.

A friend from synagogue even helped me think more clearly about my immense feelings of guilt. “What if this was God’s plan?” she said. “If you had stayed married to Mark, he would not have qualified for the benefits that pay for his care. And you’ve had time to heal from dark days. Now you have the strength to help him.”

I had been wondering whether my prayers for Mark and our family were heard. Now I could see how 9+ were there, even in the midst of darkness.

Mark’s facility specializes in mental health and brain disorders. He receives excellent care, even as his abilities decline and he has become less responsive and started using a wheelchair.

Julie now serves as a cantor at a synagogue outside Chicago and visits Mark twice a month. I visit several times a week. The days of our long conversations are over. Yet that time with him has become a highlight of my week.

To my amazement, I have found myself falling in love with Mark all over again. Maybe I’d never stopped loving him, hoping against hope that the frightening changes he underwent would disappear, that the real Mark would return.

We listen to music, eat chocolate, share hugs and kisses. Mark always smiles when I arrive. So do I. Sometimes he dances in his wheelchair.

The idea for the concert came to me one day while rehearsing with a string quartet at Tabernacle Presbyterian. I suddenly realized that Mark had made all four instruments in the quartet. An idea came to me.

“Wouldn’t it be wonderful to do a concert featuring all Womack instruments?” I said.

“Let’s do it,” said the music director at the church. “We’ll host it.”

So here we were, gathered in this beautiful sanctuary to honor a talented musical craftsman. A wonderful husband and father. A blessing to everyone who knew him.

Thirteen musicians from around the United States had come to play their Womack violins, violas and cellos. The concert was free, but audience members donated $2,000, which would go to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Sitting onstage, gazing at the expectant faces in the pews, I had to stop myself from crying. Mark didn’t understand exactly what was happening. But I knew he was feeling the love in this church.

The music was beautiful. Mark smiled and swayed in his seat. During pieces I didn’t play, I sat beside him and held his hand.

Our daughter concluded the concert with a song called “T’fi lat HaDerech,” which means “traveler’s prayer” in Hebrew. The song is the composer’s interpretation of a Hebrew prayer for a safe journey. She was accompanied by an ensemble of instruments made by her father.

I am comforted by these words from the prayer: “May we be sheltered by the wings of peace. May we be kept in safety and in love. May grace and compassion find their way to every soul.”

I know that grace and compassion have found their way to Mark’s soul. And to mine.

Through Mark, God has shown me a deeper form of love. A love that sees everyone as worthy to be loved. It’s how God loves us. And how I plan to love Mark now and always.

Read more: 5 Ways Music Can Help People Living with Dementia

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.