I have this recurring dream. I’m driving a car on a racecourse with no one else around. There’s a turn up ahead. I try to steer, but I bang into a wall. Then another. Desperately, I try to get control. But it’s no use. No matter how hard I try, I keep careening off the walls, losing control.

It’s taken me a long time to understand that dream. But a young boy I met 25 years ago started me on the right track.

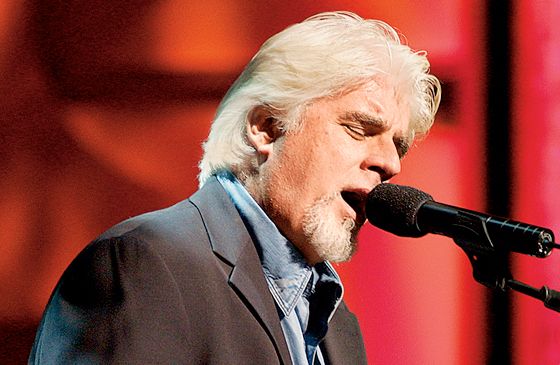

In 1980 things couldn’t have been better for my band, the Doobie Brothers. Our album Minute by Minute had sold three million copies and we’d won four Grammys for the song “What a Fool Believes.” I should have been on top of the world. Truth was, I’d never been so unhappy.

We’d just finished our annual benefit concert at the children’s hospital in Palo Alto, California, and had gone upstairs to visit a 14-year-old boy with cystic fibrosis who wasn’t expected to live much longer.

The moment we walked into the boy’s room, his face lit up. His parents stood near the window. The boy had to lie face down because that was the only position in which he could still breathe, but he never stopped smiling and joking as we signed autographs and played a couple of numbers.

How can he look so happy when he’s so sick? I thought. He’s so young.

Fourteen. That’s how old I was when I wrote my first song with my dad, called “My Heart Just Won’t Let You Go.” Dad drove streetcars and buses in St. Louis for a living, but his true love was singing.

Sometimes I’d ride with him on the morning local and listen to his Irish tenor soar above the sounds of the street. He and Mom were divorced. Mom worked long hours managing the local S&H Green Stamp store. So it was my grandmother who mainly raised me and my two sisters.

All of us sang. I played banjo and fiddled around on the piano some too. Grandma bought me my first guitar from Sears, Roebuck, and Co.—a Silvertone classic with an amp in the case.

Pretty soon I was in a band with some guys I knew. They were a little older than I was and had grown up singing gospel in church. I loved the passion in gospel songs. The music came from a place deep down.

I didn’t study music formally, but I still had my teachers: Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye. I played their records over and over, learning every note, every inflection, every feeling by heart.

After that first song with my dad, I wrote more on my own, mostly ballads. Love songs came naturally to me—maybe because I was born just two days before Valentine’s Day. Who knows? Our band would land some little gig—a church dance maybe or a community center—and I’d be thrilled.

My voice was lower than Dad’s, a husky baritone instead of his lilting tenor. I learned pretty fast that trying to direct it got me nowhere. Every show I struggled to surrender to it and let it carry me.

I moved to Los Angeles when I was 18. I got a lot of backup work, but for years I wasn’t really getting anywhere. Then I got a break to play with Steely Dan. That led to joining the Doobies in 1975. The lead singer got sick and I stepped in.

I took Dad to my first concert. We pulled up to a stadium and walked in to see thousands of fans. Dad grinned. “This is all right, Son. I think you’re doing all right.”

It didn’t really hit me until the night we won all those Grammys. A driver had been sent for me. “Could you drive up Highway 1 for a while?” I asked him. I was too wired to go home. So much had happened so fast. I’d made it. A poor kid from St. Louis with a big voice and a lot of luck.

I knew my family was proud of me. But skimming through the darkness that night, the white crests of the waves in the distance, the crisp salty air blowing back my hair, I felt lost. Do I really deserve all this? I thought. I should be enjoying this. But why does it all feel so empty?

These thoughts still haunted me months later as I stood at the bedside of a boy who would never get the chance to go on a roadtrip with his pals, take his girlfriend to prom, start his own life. Yet he was making the most of this moment, taking life on life’s terms. He filled the room with love.

I was twice his age but between all the touring and interviews, I didn’t feel as if I had much of a life. And I’d picked up some bad habits from the rock ’n’ roll lifestyle, habits I couldn’t break. I didn’t know who I was anymore. What had happened to that boy from St. Louis?

I was certain—as sure as if I were the one who was dying—that I had to make some changes.

I was known for singing love songs. What about the love in my own life? I’d been kind of dating someone—Amy, a singer whose voice I loved—but I didn’t have much time for a personal life.

I started to make more time though. I’d leave the recording studio in Hollywood at 1:00 a.m., pick up Amy and hop onto Highway 5. We’d drive into Death Valley, make camp on the desert floor and talk for hours under the stars.

One night I was going on and on about my first solo record—how I wanted everything to be perfect. Amy reached out to touch my cheek. “Look up at the stars, Mike,” she said. “They’re perfect and they’re here right now. Don’t miss them.”

Amy was changing her lifestyle. I wanted to also. I’d had some close calls with drugs and alcohol. I didn’t want to end up a rock ’n’ roll cliché—dying on silk sheets in some hotel room. I didn’t want to lose Amy. But the harder I tried to break my addictions, the stronger they became.

I’d wake up from my dream. Sweating. Heart pounding. I’m not in control. I can’t do this alone. I need help. And so I began to ask for it. From family and friends. From counselors. From Amy. And from God.

Giving up drugs and alcohol meant making room for new things in my life. Amy and I tied the knot in a big church wedding in 1983. We settled in a house just around the corner from that church and had a son and daughter.

I’d listen for the church bells every day. They reminded me of the new path my life was on. I wanted to get back to the music of my roots and be closer to my extended family.

So in 1995 we went south—to Nashville. We bought a hundred-acre farm with cows and horses and pigs—Old McDonald’s Farm the kids called it. I worked on my solo career and Amy worked on the house.

And then life took a sharp turn. Amy was diagnosed with breast cancer. There was lymph node involvement. Her prognosis wasn’t good.

One afternoon during a chemo session, I sat holding Amy’s hand, hoping the side effects wouldn’t be too bad this time. Suddenly she turned to me. Our eyes met and she gave me this sad little smile, as if to say, “I’m sorry you have to go through this.” Me? I thought. Why is she worried about me?

Suddenly my thoughts flashed back to that young boy at the children’s hospital almost 20 years earlier. I’d written love songs all my life but only now was I beginning to truly understand love. I squeezed Amy’s hand.

Her long blond hair was gone, her green eyes dull above her sunken cheeks. But she had never looked more beautiful to me than at that moment. On the drive home, Amy stared out the window a long time. Finally she turned to me. “I don’t know what I’m facing here. I mean—”

“You’re not going anywhere,” I stopped her. “You’re going to be here a long time. Everything will be okay.” To stop believing that would be to give up hope.

Amy was exhausted but wouldn’t hear of missing our daughter’s Christmas pageant. Sitting in the auditorium with my arm around her, I could feel her shoulders trembling as we watched our daughter glide across the stage in her angel wings. I turned to my wife. Her eyes were wet with tears.

She’s wondering if she’ll be here next year, I realized. If our kids will have to grow up without their mother.

I thought of meeting Amy so many years earlier. Without her, I may never have found myself. I’d let go of my old life. Now I had to let go of the future too because I couldn’t control it.

God, you gave me my voice, brought me success, brought Amy into my life when I needed her most. Help her now. Allow us to stay together as a family.

Our daughter took a bow, her wings brushing the stage. Amy clapped with all her strength. In that moment I felt an incredible strength too, of hope and love and all the blessings we receive, deserved and undeserved.

Eight Christmases have come and gone since then. Eight New Year’s. And soon, eight birthdays (I’ll be 54 this year). And I’m thankful to say Amy is cancer-free. She’s working on a new album and our 22-year marriage is stronger than ever.

You know, I still have that old dream sometimes. It happens when I try too hard to shape the future instead of taking things one day at a time. We have to let go in life. Allow a Higher Power to take the wheel and trust we’ll be taken care of no matter what. That’s how I try to live, minute by minute.

Read more about Amy's struggle with cancer.