There’s no magic formula for living longer and better. But a certain character trait makes getting older a lot more rewarding: having an open mind and heart.

Just ask David Starbuck of Chestertown, New York; Shirley Uekert of Marathon, Wisconsin; or Dave Jackson of Fishers, Indiana. These three very different people in their sixties, seventies and eighties live every day with the highs and lows of aging.

They thrive through it all by learning.

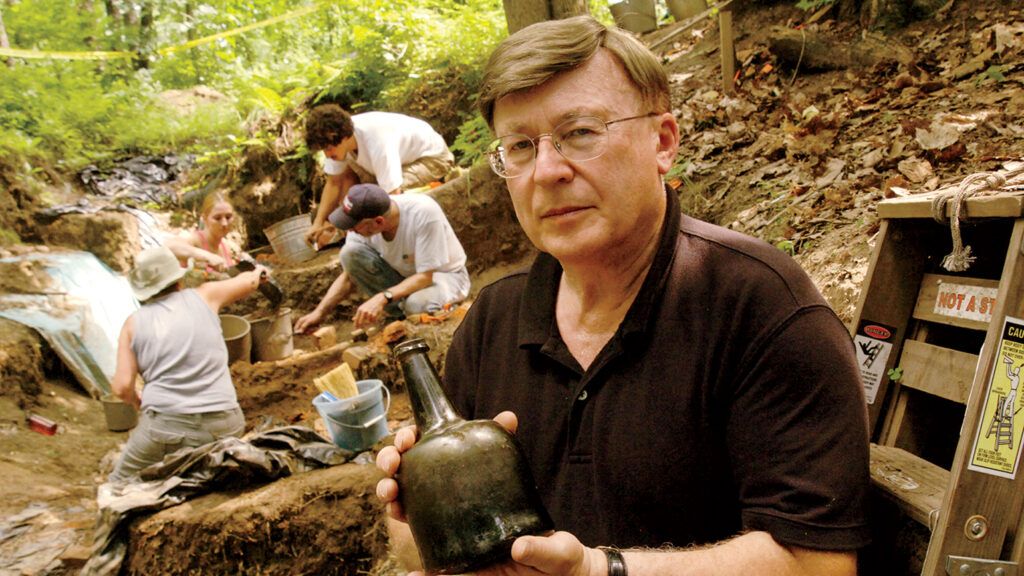

David, an archeologist, continues digging up military history in upstate New York despite a diagnosis of advanced pancreatic cancer.

Shirley, a farm wife whose husband died several years ago, defied a lifelong fear of water and learned to swim in her seventies.

Dave is a retired pharmaceutical chemist who spent much of his life in a quiet, orderly laboratory—then plunged into acting not long after his own cancer diagnosis.

All three told me it is never too late to learn a new skill, try a new experience or listen intently for whatever life and God are trying to teach you. In fact, David, Shirley and Dave described their openness to whatever comes next as a cornerstone of their vitality. They live longer and better by envisioning their lives, and their souls, as unfinished projects.

Here are their stories—and their hard-won, inspiring wisdom.

David Starbuck

Chestertown, New York

Last August, a doctor told 70-year-old David Starbuck he had advanced pancreatic cancer, a diagnosis with a six-month to one-year survival prognosis.

David had a ready comeback. “I vowed I would prove that doctor wrong and live for years,” he told me. “It’s the stubborn, ornery ones who survive. We archeologists are like that. I live for whatever I’ll discover next.”

David is not exaggeratin

g. He teaches anthropology at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire. For the past three decades, he has devoted his life to the painstaking excavation of one of North America’s most important eighteenth-century military sites: Fort Edward, near Glens Falls, New York, a redoubt for 15,000 British army troops during the French and Indian War.

David supports the work with the help of nearby State University of New York Adirondack plus grants, private donations, volunteer labor and sometimes his own money. Though he gets a university salary, David, like many scientists, must secure his own research funding.

You might think the Yale-trained archeologist, who has dug everywhere from ancient Mexican ruins to the factory where cotton gin inventor Eli Whitney once produced firearms, would be content to rest on his laurels. “A lot of archeologists never want to retire,” he says. “We are programmed toward that passionate love of discovery.”

In addition to supervising annual summer digs at Fort Edward and nearby Rogers Island, David keeps busy writing research reports, applying for grants and laying the groundwork for what he hopes will become a visitor-friendly site at Fort Edward, similar to Fort Ticonderoga and other colonial-era destinations.

He does all this while commuting weekly to Plymouth State from his family farm in the Adirondack Mountains of New York. David, a lifelong bachelor, inherited the farm from his parents. In Plymouth, he stays in a motel.

“Some people have families to live for,” he says. “I live for archeology.”

David has published almost 20 books and monographs and been written up in newspapers and magazines. He loves the attention: He was a theater geek in high school. But attention is not what keeps him working—and living—through the challenges of cancer and aging.

“Archeologists are storytellers,” he says. A single small artifact—an officer’s brass cuff link, say—can conjure an entire world from the past. “It’s no longer abstract history. You’re connecting with someone from hundreds of years ago.”

Finding and sharing those moments keep David alive—physically and spiritually. “The best site,” he says, “is always the one you’re about to find.”

Shirley Uekert

Marathon, Wisconsin

The bet was one muffin.

Shirley, then almost 70, was chatting with a bank teller. She told the teller her latest news: At long last, she was going to learn to swim. “I was petrified of the water,” Shirley says—and always had been.

The teller, Sue Werner, tried to talk her out of it. “I used to be a swim instructor,” Sue said. “When people reach your age, they can’t learn to swim.”

Had Sue known Shirley better, she might have tried a different argument. (“I’m a determined person once I put my mind to something,” Shirley says.)

“I’ll bet a muffin you can’t,” Sue said.

Shirley was in the pool taking lessons that week.

Shirley had grown up in Wausau, Wisconsin, during the Great Depression.

Her father hauled furniture for a store. Her mother stayed home. That was Shirley’s plan too. She married her husband, Eugene, when she was 25 and moved to his 240-acre farm, where he grew oats, hay and corn. Shirley and Eugene lived on the second floor of the farmhouse. His parents lived downstairs.

Shirley raised five children there and learned from her mother-in-law how to bake, can, garden and “do everything to keep farm life going,” she says.

A self-described “shy and timid person,” Shirley opened up when she met her neighbor, Phyllis Heise, whose farm was across the road. The two women have been best friends ever since, taking trips to places their stay-at-home farmer husbands didn’t want to visit.

Shortly before that bank visit, Phyllis, who also didn’t know how to swim, came home raving about a shallow-water exercise class she’d signed up for at the local pool. A chiropractor had recommended water exercise for Phyllis’s achy knee.

Shirley was dubious. Earlier that year, while visiting one of her kids in Arizona, she’d clung for dear life to three foam flotation noodles in the family’s backyard pool—in the shallow end.

Phyllis convinced her to try the class. Shirley discovered that, as long as she kept her feet planted on the bottom of the pool, she had a good time.

Still, it bothered her to watch other people her age nonchalantly swimming laps. Why couldn’t she do that? She and Phyllis talked each other into taking lessons.

“The instructor had us stand in three-foot water and float on our stomachs, and I was terrified,” Shirley says of the first lesson. “We wanted to use the noodles, but she would not allow us to. She said we’d become dependent. We had to keep practicing and practicing. Once I almost drowned. I still made myself do it.”

Eventually she worked up enough courage to venture into five-foot water. Then she paddled into the nine-foot deep end. At last she swam an entire lap. Two months later, she swam a mile.

I asked Shirley, now 87, where she gets her determination. “I am very strong in my Lord,” she says. “I depend on him for everything. You need spiritual strength to keep going.”

A homemade muffin helps too. Sue honored her bet and even made an extra lemon poppy seed muffin for Phyllis.

“That muffin tasted pretty sweet,” Shirley says.

daughter Emily

Dave Jackson

Fishers, Indiana

About five minutes after I started talking to Dave Jackson, he was telling me about his laboratory work for pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly and Co. I lost track when he got to the part about developing “systems to monitor the assay.”

Dave is even-tempered, measured, precise. “I have always been in the chemistry lab,” he says. “I love doing science. The lab fit my personality.”

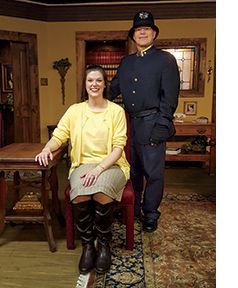

Shortly after Dave retired, his 31-year-

old daughter, Emily, asked him an unexpected question: “Hey, Dad, would you be interested in trying out for a play?”

Emily had been cast in an Agatha Christie play at the community theater. She worked for an insurance company but acted in her spare time. Dave and his wife, Leanne, lived nearby.

Dave’s answer was equally unexpected: “Sure, why not?”

It wasn’t just Dave’s chemistry background that made acting a surprise. A few months earlier, Dave had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. The cancer was a less aggressive form, but he had a monthly treatment regimen to stop the growth of tumors and manage secondary symptoms. (As you might expect, Dave described this treatment in great scientific detail.)

Why audition? He had done some acting in high school. When his kids were younger, he’d appeared in a few homemade plays for a church fund-raiser.

There was also the benefit of spending more time with Emily. The two saw each other mostly on Sunday evenings, when Dave dropped by Emily’s apartment for a weekly movie night. The two of them like the kind of action movies that Leanne “isn’t into,” Dave says.

But there was something deeper. The 66-year-old says throughout his life, and especially after the cancer diagnosis, he has felt that “God wants me to learn something. He’s trying to teach me.”

For Dave, life is for learning. School, work, marriage, fatherhood, church, retirement, cancer—each milestone is a chapter in God’s unfolding story. In Dave’s view, openness to new experiences, even something as offbeat as acting, is staying alert to God’s teaching.

Dave landed the role of Constable Jones, who has four lines and finds what turns out to be a vital clue. He and Emily rehearsed during the drive to and from the theater. Dave got to watch his daughter shine onstage. His theater friends rallied around him as he underwent treatment. He has since acted in one more play and plans to audition for another this summer.

Dave says acting has deepened his relationship with Emily—and with God. “I feel as if God’s not done with me yet,” he says. “I’m still around and, in the meantime, getting lessons about love.”

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.